By Eric K. Curtis

All adventure stories require their protagonists to take a journey. Aspiring heroes must leave their homes and cross a threshold, pass through a portal, to get to the land of their dreams—the place where they achieve their true potential. The Pevensie children access Narnia by clambering into a wardrobe. Harry Potter boards the Hogwarts train by leaping through the wall at Platform 9 ¾. Milo arrives at the Kingdom of Wisdom by driving through a phantom tollbooth. The specifics vary, but the pattern abides: Dorothy follows a yellow brick road. Alice squirms through a rabbit hole. Neo swallows a red pill.

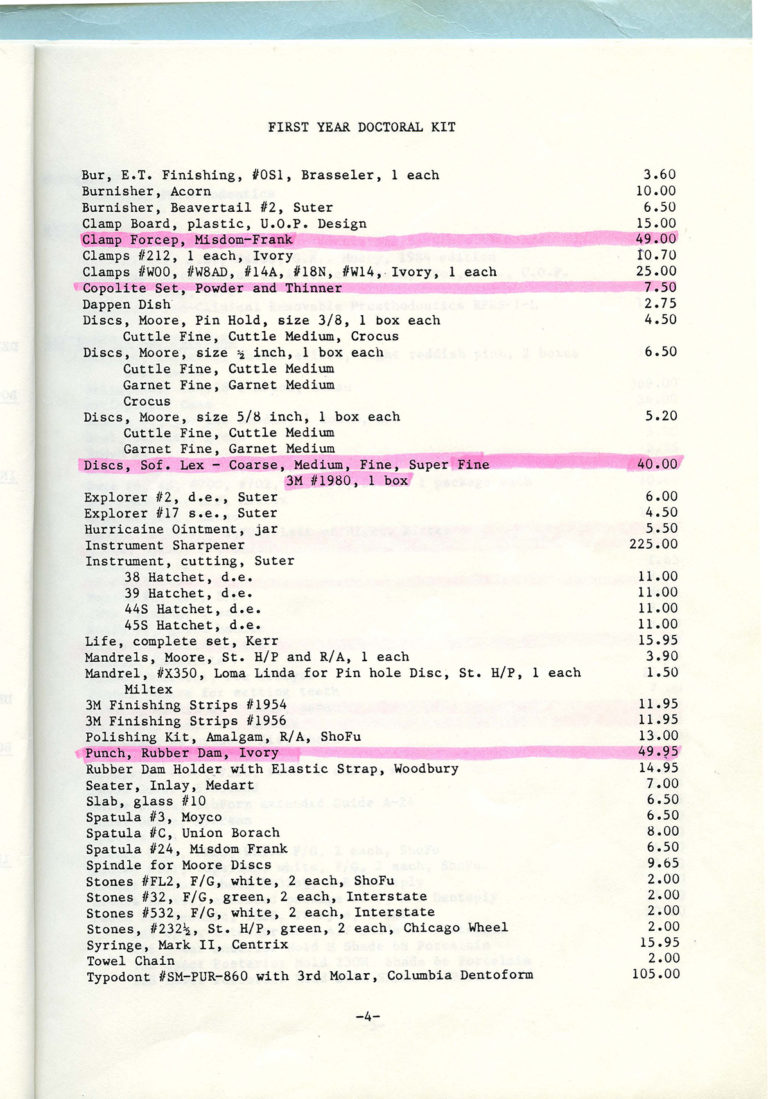

For students at the Arthur A. Dugoni School of Dentistry, the phantom tollbooth is called the student kit. The kit, of course, is that collection of equipment, supplies, instruments, books and materials issued each year for the purpose of shaping bewildered, imprecise civilians into dentists. The kit’s transformative aspect should not be underappreciated. Each class’s collection of stuff, from hand instruments to articulator parts to polishing tips, represents the tools of identity change.

Students access their armamentarium through a solemn ceremony, although few of them recognize it as such. The first stage, admittedly more memorable in the years before words got lodged in the cloud, involves the symbolic bestowal of knowledge, otherwise known as buying books. In July 1982, I presented myself at the Student Store, where staff members issued me a daunting stack of texts. Some, like Dr. Roy Eversole’s oral pathology tome, would become reliable companions over the next 37 years, while others, such as (cough) the removable prosthodontics volume, would never shed their cellophane wrap. The store lent me a wheeled dolly to push the paper up the hill to my apartment.

The second stage of the student kit ceremony is the figurative transfer of ability, otherwise known as unpacking supplies. I congregated with my yet-unknown classmates in the Webster Street third-floor, pre-clinical laboratory, in between rows of black-topped laboratory benches, where we liberated our piles of paraphernalia from their shrink-wrapped, zip-locked, clamshelled and/or envelope-sealed cocoons.

All heroes, especially those staring down a plethora of unknown objects, need a mentor, and in this preliminary rite of passage ours was former Executive Associate Dean and current Professor of Preventive and Restorative Dentistry Dr. Robert Christoffersen ’67. “I always tried to reassure the new students,” Christoffersen says, “and attempted to provide the message that they will one day know what all the items will be used for in dentistry.”

The tone of that message impressed me as much as the substance. Understanding that I would become intimately acquainted with these bizarre accoutrements made their unfamiliarity all the more weird. But Christoffersen’s mellifluous voice sounded warm, amused and slightly meditative. His calm approach felt wise, and even omniscient, as if he were channeling, all at once, Gandalf, Obi-Wan Kenobi and Pat Sajak. My confusion at pawing through mysterious packages faded as I compiled my gear. (The process of identifying and cataloging things is itself therapeutic.) I went home that day with a curious sense of hope.

Some kit contents are evergreen. Today, students still get a Boley gauge and a flexible mixing bowl. They still learn dental anatomy at the tip of their Tanner carvers, although none of their wax-ups will turn to gold. But much of the kit I absorbed almost four decades ago has vanished. There are no glass slabs. No crucibles or casting rings. No rouge. No tiny vials of gold foil.

My kit’s organizing principle took the form of a bookstore-issued wooden box. It was something like a large tool chest or jewelry case, a traveling cabinet fitted with lockable drawers and compartments for instruments—chisels and hoes and excavators and condensers and curettes—and medicaments like copal varnish and squirmy, hard-to-hold objects, like my Bunsen burner with its brick-colored hose. Following the pattern of a generation or two of students before me, I carted my case from pre-clinical lab to clinic. The box was my rabbit hole, a tunnel from the clammy caves of Clinic C to the sunlight of dental practice. I still keep my box in my office, where people occasionally offer to buy it.

In the mid-1990s, the box disappeared from the student kit, rendered obsolete by two developments. One was the creation of efficient storage spaces incorporated into a computerized, clinically realistic pre-clinical simulation lab. The other involved sea changes in equipment, technology and priorities.

In 1982, I bought my own instruments, including an air-turbine handpiece—complete with spring-loaded hex wrench for tightening burs—and a geared slow-speed model with both nose cone and latch grip heads. I scratched my name onto the shanks of each with a revved-up 330 carbide bur. A name was a good thing on a pass-around lab spatula, but keeping track of an expensive high-speed drill was easier because I never sent rotary instruments in for sterilization. Hand pieces, in fact, could not be autoclaved until nearly a decade after I graduated. Instead, I carried—in my box—a glass jar of alcohol-soaked gauze pads to wipe off the blood and grit.

Infection control and sterilization protocols have long since come to dominate the center of gravity for appropriate care. Consequently, the school owns the equipment and supplies that students use in clinic, including handpieces, most of which are electric. “All instruments are sterilized, packaged in cassettes and bar-coded at our central sterilization area,” explains Dr. Sigmund H. Abelson ’66, former associate dean of clinical affairs and chair, Department of Clinical Oral Healthcare, “and then distributed to the clinic dispensaries, where students check them out as needed and return them when the procedures are completed.” The school charges an instrument use fee.

This year’s kit includes a bleaching system and a curing light, but much of the equipment available to students won’t fit in a box anyway, or comes in its own—things like CAD/CAM units for milling restorations, digital impression scanners, lasers, CBCT cone beam imagers and 3D printers that produce surgical implant-placement guides.

Neither do books necessarily go on a shelf. Students now read many texts online. Other disappearing acts include lab time and alloy restorations. Students perform fewer laboratory procedures, including denture set-ups, than did past generations. While they can still do amalgams, dramatic improvements in adhesive dentistry and strong patient preferences mean that students almost exclusively place composites.

While first-year students still get a robust kit, the contents of that kit, reflecting the school’s entire educational process, remain in perpetual motion—compared not just in a broad arc between, say, 1982 and 2019, but every single July. The kit is continually recalculated according to the innovations in science, advancing concepts in care and instantaneous communication that coalesce to push new elements and methods to the forefront. “This has become more exciting in recent years as dentistry has faced the rapid evolution of dental materials,” Dr. Christoffersen says. “When it comes to materials, much of what we teach today will most likely change in one year.”

For all its weight as a portal of personal change, then, the student kit also functions as a marker of dentistry’s evolution. Dental education is more comprehensive. Students now learn to screen for systemic diseases such as diabetes. They manage caries—which previous generations handled by finding dark or soft spots and passing out floss—through a complex assessment of each patient’s risk factors, including socioeconomic status; oral health history; oral environment dangers, from tooth shape, position and surface area to frequency of acid exposure; and the presence of protective elements, from the body’s own immune system (read: salivary flow) to chemical enhancements, such as topical and systemic fluoride, dietary xylitol, chlorhexidine and calcium and phosphate paste.

The Dugoni School of Dentistry prides itself on preparing its students for state-of-the-art dental practice, a position that represents not only an array of cutting-edge technologies but also a holistic mindset. “We instruct our students that we only provide comprehensive care to patients,” Abelson says. “That is, we do not provide ‘limited care,’ but rather treat the whole patient to make them healthy.”

Assembling a comprehensive-care kit involves a perennial cycle of research, consensus and selection. The Student Store, for which kits constitute 75% of annual sales, begins planning, following input from faculty and administration, about nine months ahead. An array of products must be identified, ordered, tracked and tabulated. In May and June, the store receives some 2,000 shipments of books (yes, there are still some physical books) and supplies and begins staging 620 individual items for packaging into—as of the 2019 count—314 kits for summer disbursement to first-year, second-year and International Dental Studies (IDS) students.

For all its weight as a portal of personal change, then, the student kit also functions as a marker of dentistry’s evolution.

“The nature of the student kits has changed, often due to University policy,” says David Swanson, procurement and inventory manager. “But, the need for our dental students to have doctoral kits will remain, and with it the obligation to manage the cost while still providing the necessary tools and materials that students require for their fast-paced and challenging education here at Arthur A. Dugoni School of Dentistry.”

In the midst of relentless refinement, one remarkable aspect of the student kit has not budged—its cost. The world becomes ever more expensive, but the price of the Dugoni School of Dentistry’s student kit represents a well-managed constant. The Class of 2022’s first-year kit, including tax, comes to $11,624, essentially the same amount as the Class of 2006’s.

The kit’s fiscal stability streak stretches even longer. The 1963 kit sold for $1,372, which, according to an online U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index inflation calculator, had the purchasing power of $11,485 in 2019. I bought my 1982 kit for around $5,000, equivalent to $13,000 today. The real price of the Dugoni School of Dentistry’s student kit, in other words, has remained remarkably stable across six decades.

The kit’s cost is easy to measure. Its value, however, remains inestimable.

_____________

Thanks to David Swanson, procurement and inventory manager, and Sandra Shuhert, Design and Photo Services, for their contributions to this article.

Eric K. Curtis ’85 practices general dentistry and teaches college English in Safford, Arizona.