By Eric K. Curtis, DDS, MA

Dr. Nathan Yang ’06 was floored when his receptionist disappeared. Yang and his wife, Dr. Joanne Jeng ’04, had been thrilled about the practice they bought in San Francisco in 2008. But the excitement soon turned to dismay when the woman working the front desk left without warning, creating both a security breach and a practice management headache. Yang, who teaches part-time at the Dugoni School of Dentistry, thought long and hard about his options. Instead of hiring a new receptionist, he installed an electronic front desk.

Yang’s solution involves two separate Web-based services, Demandforce and ZocDoc, the latter of which was suggested to him by Pacific alumnus Dr. Jared Pool ’09. Together, the services create an integrated system for managing patient flow. The system puts Yang’s practice among the first five dentists in his zip code to appear during Google searches. It invites patients and potential patients to view available openings online. It prompts patients to make, confirm, cancel and reschedule their own appointments, or leave a message for his assistant to call them back. It then sends patients appointment reminders by email or text message.

This system, synchronized with the office’s existing scheduling software, allows Yang and his assistant to monitor their appointment books and interact with patients from any location. Much of this patient interaction occurs in the operatory. “My assistant can make appointments and handle patient questions while I’m looking at X-rays,” Yang says. The office computer generates recall reminders and even sends patients surveys via smart phone after appointments to gauge their experiences, transforming Yang’s patient base into a private, interactive social medium. “If I get a bad comment,” he says, “I have a staff meeting right away to fix the problem.”

The two services together cost less than $7,000 per year to maintain. “I realized I could either set up an electronic front desk,” Yang says, “or hire a new person at $25 an hour, with the accompanying ebb and flow of emotions that hurt us before.” With his virtual receptionist up and running, Yang discovered that his scheduling improved. Open spots filled up with less hassle. His no-shows dropped. “I haven’t really had a front-desk employee now for four years,” he says.

Yang concedes that some people are “weirded out” by his technological leap of faith. “It might seem sort of ‘out there,’” he says of his lack of a human receptionist, but insists he is technologically conservative. He doesn’t maintain a conventional website, or an office Facebook presence, and he doesn’t participate in crowd-sourcing platforms such as Yelp. “I don’t believe in tech for tech’s sake,” Yang says, “but I have to ask myself what’s reasonable. I want to be accessible.” His system, he says, is low key and professional, and not self-promoting: “There is no way my patients can’t get in touch with me. I’ve found a way to communicate without being overbearing. It’s fast, easy and discreet.”

[pullquote]The upshot is this: Nate Yang runs his practice over the Internet using his smart phone. Welcome to the brave new world of communications technology.[/pullquote]

Dr. Parag Kachalia ’01, assistant professor and vice chair of pre-clinical education, research and technology in the Dugoni School’s new Department of Integrated Reconstructive Dental Sciences, keeps his finger on the pulse of technical innovation. Communication is the essence of both education and patient care, and the Dugoni School of Dentistry has worked hard to attune the flexibility and sensibilities of its humanistic philosophy to changing technologies. “We try to analyze not just what’s happening now but also anticipate conditions two to five years out,” Kachalia says.

What’s happening, of course, includes new technology. The dental school, which previously pioneered clinical studies of Invisalign®, is currently testing a system for digital dentures with a computer-based occlusal scheme. On the first appointment, the dentist takes a traditional impression and creates a jig to capture occlusal records; on the second appointment, the dentist delivers the denture.

Such technologies may improve both clinical practice and the quality of the educational experience itself. The 3M ESPE company recently donated to the school 12 Lava Chairside Optical Scanner (COS) devices, digital impression machines that let dentists produce a three-dimensional model of a patient’s mouth. The fact that students—bringing long-practiced video game-playing skills to bear—can easily manipulate the hardware to visualize the mouth’s hidden recesses in magnified 3-D signals a truly collaborative approach to education. Developments such as the COS, Kachalia says, “allow us to dramatically bring the intraoral environment out of the mouth and in front of everyone.”

But Kachalia explains that the dental school’s sensitivity to trends in technology also involves a close reading of how people accept and use that technology. Accordingly, instructors are exploring the educational opportunities of social media, preparing virtual classrooms on Facebook and experimenting with communications via a Twitter feed. (Email, it turns out, is so ten minutes ago—while electronic messaging used to be the vehicle of choice for rapid information exchange, people have become bombarded with spam to the point that many mostly ignore it.)

To be sure, social media represents both rewards and risks for dentistry with pitfalls lurking next to the promises. Facebook, as Kachalia describes it, may be “this generation’s gathering around the coffee table,” but confidentiality is a concern, as are implications for ethics and professionalism. “Facebook has great educational potential,” he says. “We need to learn how to properly navigate it and put up appropriate filters.”

Yang believes that one danger of social media for practitioners is the temptation to chase immediate gratification; some may see those communication channels as a vehicle for making quick money without consequences. Another risk lies in giving the public open access to pass judgment on a dentist’s practice. The instant interactions that social media provide invite raw, unvarnished comments that can severely affect a dentist’s reputation—comments that patient confidentiality laws prevent the dentist from fully addressing. When you give the world a free canvas to paint on, Yang says, “You have to take the bad with the good.”

[pullquote]E-mail, it turns out, is so ten minutes ago…[/pullquote]

Yelp, the user review website, also presents a double-edged sword. While unedited patient testimonials can be a source of free advertising, the ability to post anonymously can provoke abuse, because, true or false, statements posted online may come to define a dentist. “Sites like Yelp, Twitter and Facebook are powerful tools,” Yang says, “that can quickly build or tear down your practice.”

“You can’t base your whole professional identity on whether you have two or four stars,” observes Kachalia, referring to Yelp’s rating system. “We need to be careful as a profession to create value within ourselves.”

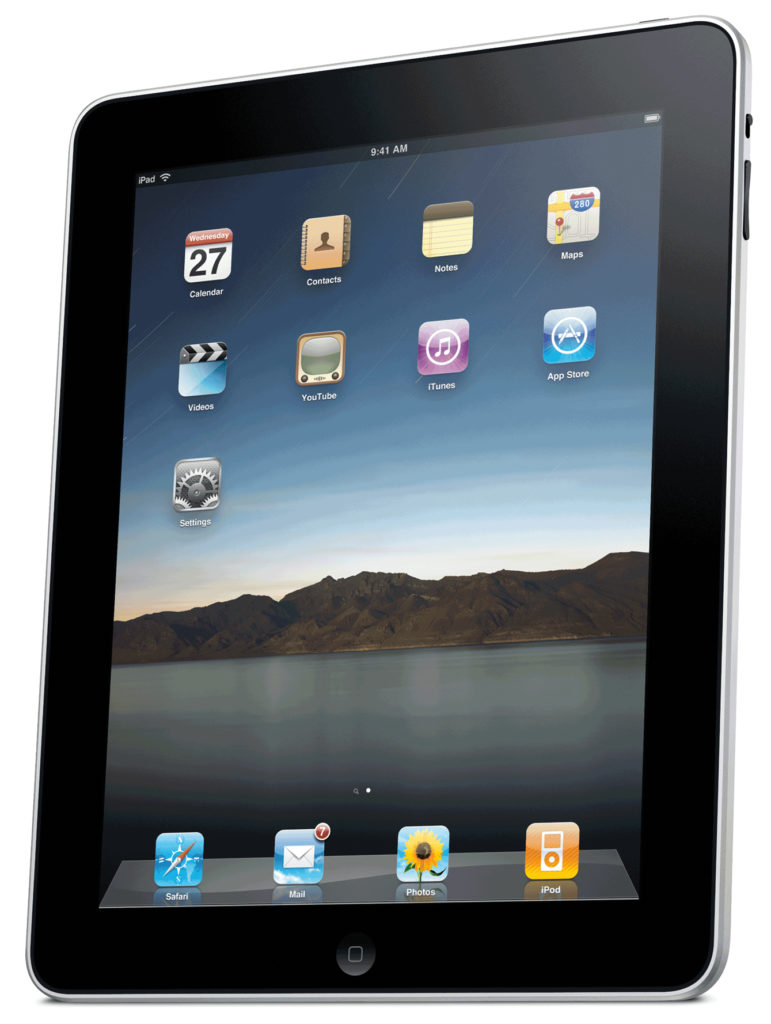

One of the complications of this everyone-in-touch age is that communication is often multidirectional. “At school you have to bridge communications in a triangle, from faculty to students, then from students to patients,” Kachalia says. In one such bridge-building venture last year, the school introduced iPads, loaded with an application aimed at communicating with patients, into the Main Clinic. Students pull up the DDS General Practitioner patient education app to show photos, diagrams and animated images of common oral conditions and dental procedures, as well as present clinical findings, prevention recommendations and treatment plan options.

The electronic world has altered not just how students teach patients but how the faculty teaches students. Students today learn differently, Kachalia reflects. Having grown up in an environment of continuous stimulation, they may chafe at the traditional “sage-on-the-stage” lecture format. They are more comfortable with a two-way model of education. They want to be able to respond. More than just facts, they want applications. And because students have quick access to information, instructors must keep very current. “I can be lecturing,” Kachalia says, “and a student might be Googling to verify what I’m saying.”

Yet for all the potential insecurities that technology may serve up, even mature Pacific alumni remain enthusiastic about its possibilities. Dr. Kenneth Frangadakis ’66 is founding partner of a multi-specialty dental group in Cupertino, California, most of whose partners and associates are also Pacific grads. “As dentists,” he says, “we have to stay well educated and try to stay ahead of developments. If you are just keeping up, you’re falling behind.”

While Frangadakis admits he’s a “hybrid” dentist—“I write in the chart, and the staff puts it into the computer”—he keeps a careful eye on new developments. His current favorite clinical technologies include digital X-rays (“We’re upgrading from phosphor plates to sensors”), the iTero digital impression system and the Onpharma buffering setup for local anesthetic invented by Pacific alumnus Dr. Mic Falkel ’87, which Frangadakis liked so much that he invested in the company. “It really works,” Frangadakis enthuses. “The anesthetic is fast, it doesn’t hurt and it’s very profound.” The next piece of equipment on his list: “We need to get a three-dimensional imaging machine.” Frangadakis is also planning to incorporate an automated patient messaging software system, similar to Demandforce, called Smile Reminder.

Pacific alumni agree that no amount of technical innovation can compensate for poor patient care or sloppy interpersonal skills. “There is something to be said for treating people like family,” says Yang. “Regardless of technology, you still have to gain and keep people’s trust. You have to believe that it’s a privilege to treat people and an honor to make a living by helping people.”

“Successful practice is about giving value and service,” Frangadakis says. “Take care of people the way you want to be taken care of.”

Eric K. Curtis ’85, DDS, of Stafford, Arizona, is a contributor to Contact Point and is the author of A Century of Smiles, a historical book covering the dental school’s first 100 years.

Pictured from left: Mark Nelson, Scientific Affairs Manager, Lava C.O.S., Dean Ferrillo, Marc Geissberger, Parag Kachalia and Foroud Hakim display the new Lava Chairside Optical Scanners