By David W. Chambers

Dr. Dale Redig and his wife, Diane, greeted Dr. Craig Yarborough ’80 and me at the front door of their cozy house in Stockton, California. We chatted a long time—there was much to say about his time as dean of our dental school from 1969 to 1978 as well as all that has happened since. Diane offered many additions and recollections along the way; they were then and continue to be a formadable team. There were pastries and fresh strawberries. It was exactly as it should be.

One of the reasons for the visit was to acknowledge Redig’s recent honor from the American College of Dentists—the Lifetime Achievement Award, marking his 50 years of service to the profession. What that means in practical terms is that he started as a leader in dentistry at an early age, and then kept going.

Redig, who became dean at age 39, hired me in 1971 so it was fun to talk about the old days. He was almost wistful about the challenges he encountered when he got to San Francisco, but there was still a sense of urgency in the stories he recounted. The College of Physicians & Surgeons, after nearly 70 years of going it alone, had merged with the University of the Pacific in 1962, and there were many issues to work out. The dental school faced the accreditation process, including a site visit, very shortly after Redig arrived. And it was not an ordinary visit. The school was on conditional status: unless it could be demonstrated that changes had been made to bring it up to the standard, there was a very real possibility that we would lose our accreditation, a fatal blow that would almost certainly force the school to close.

“Yes,” Redig said, “we had to make changes very quickly. Not everyone liked it at first, but I always gave clear explanations about what we were doing and why.” The story about many of the windows in the building on Webster Street being covered and painted over and how he ordered them to be opened are true. It is also a fact that he organized a brigade of students and administrators to paint parts of the school just before the accreditation site visit team arrived. On the academic front, he brought four-handed dentistry from University of Iowa to Pacific as he was chair of the Department of Pediatric Dentistry at Iowa and DAU was taught in his department. An entire floor of the new dental school was devoted to research and Redig hired Dr. Gunnar Ryge, then immediate past president of the International Association for Dental Research, who styled himself the “assistant dean in case of research.” Additionally, Redig started the tradition of a retreat at Asilomar in 1968, a 50-year anniversary the school celebrated this past February.

There is a paradox in what Redig set out to accomplish. Although he initiated some swift, dramatic changes, decades later we are still working to realize many of his goals. That is not because Redig was a slow starter. Rather, it is because he focused on the fundamentals. There are issues that are central to dental education—challenges that emerge continuously in new forms and separate the schools struggling to remain open from those growing to greatness.

This is the story of six of the goals that Redig laid out half a century ago: (1) a comprehensive care clinical model, (2) humanism, (3) curriculum efficiency, (4) a functional physical facility, (5) financial stability and (6) meaningful initial licensure examinations. These stories will be told by current faculty members who were not yet part of Pacific when Redig finished his tenure as dean in 1978 to become executive director of the California Dental Association.

[pullquote]“I always gave clear explanations about what we were doing and why.”[/pullquote]

Comprehensive Patient Care

Dr. Des Gallagher, group practice leader and newly named executive associate dean, says he recalls hearing that dental school clinics were once arranged so that the school managed all patients and allocated them to specialty areas by the half day. If it was Monday, students did gold foils, on Tuesday afternoon it might have been endo. Patients generally had multi-visit procedures completed by the same student, but their overall care was divided among students. If there were thoughts of sequencing treatment or providing comprehensive care, there was really no way to achieve it.

“I simply cannot imagine learning dentistry that way,” Gallagher says. “Prevention, patient management, treatment planning and so much of what we understand today as appropriate care must have been learned after graduation. We are in the health care business; not the business of doing procedures for their own sake.”

A major part of the change has involved building stronger, better relationships between students and faculty. Students now work in teams of 18 each of second- and third- year students, five International Dental Studies students and two Dugoni School hygiene students. Teams of faculty work with distinct groups of students and patients providing continuity of care, and group practice leaders are there to coordinate everything. There is heavy investment every quarter in cross training so that faculty present current and standardized approaches to dentistry.

The equipment and support are vastly different from a half century ago. When Redig arrived, students brought their issued wooden instrument box and showed up in clinic with everything (it was hoped) that would be needed for the day. Now we have electronic medical records, digital imaging, CAD/CAM, microscopes for endo and everything the modern dental office is equipped with.

Redig brought a comprehensive care model with him from University of Iowa, College of Dentistry and it was implemented by Dr. Jim Pride, clinical dean, and the founding team of group practice leaders in 1971: Drs. Del Byerly, Ron Borer, Robert Christoffersen ’67 and Roland Smith. Each new clinical dean—Drs. Christoffersen, Borer, Richard Fredekind and Sig Abelson ’66—built on this tradition.

Humanism

“As a student, I was never treated the way I saw students treated when I arrived at UOP,” said Redig. Students were told what to do, but not why, and they were humiliated in front of patients. Lab work that was not up to standard was publicly destroyed. But the worst abuse was favoritism. Faculty had protégés who received special attention.

“I simply would not stand for that,” said Redig [a phrase he used consistently throughout our visit]. “A few faculty members left because they were probably there for their egos rather than to teach. But most came to realize that respect is essential to professionalism.”

Current third-year student Will Keeton, Class of 2018, reports that at first he took the Dugoni School of Dentistry’s humanism for granted. “I was respected and that made me want to participate in the profession and to give more.” Keeton started volunteering—something people avoid if not appreciated. He became his class representative to the American Dental Education Association which coincides with his role as a student representative on the school’s Curriculum Committee, and met students from other schools. “Would you believe there are dental students at other schools who do not even know their dean’s name?” he asked incredulously.

[pullquote]If it was Monday, students did gold foils, on Tuesday afternoon it might have been endo.[/pullquote]

“The great difference at Pacific is that everyone has a voice,” says Keeton. If students see a better way to conduct a class, provide patient care or become involved in student life or community service, they just speak up and the next thing they know, they are part of the solution instead of being on the grumble squad.

The scope of humanism has increased steadily during the past 50 years; from the early emphasis on a positive teaching relationship between students and faculty, to including patients, staff and others in all our relationships. Yes, Redig realized that he was redistributing power, but he also started the process of multiplying dignity and collaboration. Now it makes sense to speak of our being a family. As Dean Emeritus Arthur A. Dugoni ’48 has said so clearly, “This is how Pacific grows people, and especially leaders at every level.”

Curriculum Efficiency

The Dugoni School of Dentistry has the only 36-month DDS or DMD program in America. It also has the nation’s first three-year baccalaureate dental hygiene program and a popular IDS program, offering a two-year program for individuals with dental degrees from other countries. Because the Dugoni School is also among the schools with the highest clinical productivity and yields (proportion of students passing all requirements, including national and state boards necessary for licensure on time) no one can say we do it by cutting corners.

Dr. Leroy Cagnone ’59 was the architect of the original three-year curriculum. In his personal and unassuming manner, he asked faculty members to explain exactly why they needed so many hours in the program. And he would not accept “that’s the way we always did it” or “that’s what I know best” as justifications. For the most part, instruction that could not demonstrate its usefulness to the next level in the curriculum or to clinical practice was dropped.

Dr. Daniel Bender, current assistant dean for academic affairs, has led accreditation and curriculum revisions here for years. He says it is all about focusing on outcomes and adjusting the process. “We have more resources than were ever imagined when Dr. Redig was dean: computers for careful tracking of individual student accomplishment, faculty who have received advanced training in education and business, curriculum development experts, staff to coordinate individualized instruction and students who are motivated and not passive.”

In the 19th century, dentists learned by apprenticing to practitioners. For efficiency, part-time educators grouped together in the first half of the 20th century to form schools, originally for their own profit, but they kept the model of “you can only become a dentist by listening to and imitating me.” That was starting to change by the time Redig came to Pacific. The emphasis shifted to organizing instruction around the characteristics dentists needed to enter practice. The dental school pioneered competence-based dental education, also called student–centered education.

[pullquote]…respect is essential to professionalism[/pullquote]

“When we focus on what students need to learn instead of what faculty want to present, flexibility automatically leads to efficiency,” Bender suggests. “The trick is to stop thinking that learning comes prepackaged in small, faculty-led units called courses.” Under Dr. Nader Nadershahi’s leadership when he was academic dean, the Dugoni School of Dentistry started to think of the curriculum in terms of themes or major dentist characteristics, such as clinical and biomedical sciences and professionalism and personal development. These “big buckets” make it easier to be flexible and to constantly update the curriculum.

Redig says, “It was obvious that we needed to go to year-round instruction. The summers were a waste and an interruption to learning and patient care, and it was an advantage to make full use of the physical plant year round.” The Class of 1974B was the first class to graduate from the three-year program. Students saw a chance to enter practice a year earlier, faculty appreciated year-round compensation and the University recognized the economic advantages of this system. Other schools tried the model in the early ’70s, but only Pacific has been able to make it work.

Physical Facilities

Redig was keenly sensitive to improving performance by making the physical space better. The dental school’s Pacific Heights’ location had originally been selected as it was across the street from Pacific Presbyterian Hospital and Stanford Medical School with early hopes of affiliating with that school. However, Stanford Medical School moved to Palo Alto, opening the door for the College of Physicians and Surgeons to amalgamate with University of the Pacific. Negotiations to begin a University of the Pacific Medical School with Pacific Presbyterian Hospital were eventually abandoned.

Redig, with the help of Pride and Christoffersen, constantly enhanced the building at Sacramento and Webster Streets. First was the Pediatric Dentistry Clinic, redesigned to accommodate four-handed dentistry. That was followed by a new patient entrance, new clinic chairs and updated surgery, emergency and screening clinics. Extramural programs were started in Union City, the tiny town of Elk on the Mendocino coast and other sites to promote community service—ultimately seven community clinics in all.

Dr. Richard Fredekind, executive associate dean and former clinical dean, explains how our new facility South of Market has allowed the school to continue Redig’s program of fitting form to function. “We have been able to consolidate. All services are on the same two levels and they are integrated electronically.” The old typodont on a rod that was once the staple in the preclinical lab has been replaced with patient simulators with the same delivery system as found in the clinics. The IDS class shares the same physical space. The operatories in the clinic are also larger in order to accommodate faculty and staff, two computer screens and diagnostic and other equipment.

University Relations

The College of Physicians & Surgeons was the last dental school forced by the Commission on Dental Accreditation to find a university home. There were some new relationship details to work through on both sides. University of the Pacific is among only about two dozen universities in the United States that have small, non-research intensive, residential liberal arts schools with professional satellite programs such as law, audiology and dentistry. The dental school is unique among Pacific’s professional schools because its separate location, in a large city with a high cost of living, requires some duplication of services such as security, computers, human resources and public relations. It is also unique because between 25% and 30% of the operating budget comes from managing a patient care clinic.

Redig worked to broaden the allegiance of the P&S alums who had no special reason for loyalty to Pacific. Dr. Art Dugoni continued this public relations work and built our foundation into the most philanthropic unit in the University. Beginning with Redig’s deanship, the dental school has never failed to run a surplus budget and to contribute to the economic health of University of the Pacific.

Redig recounts some tough negotiations at the beginning as both the dental school and the University worked to understand their different cultures and different fiscal systems. “In the end, (University President) Stan (McCaffrey) and I became good friends, but that took a lot of back and forth because we were each trying to ensure the integrity of our programs.”

Current dean, Dr. Nader Nadershahi ’94, says “such challenges will always be with us. In changing times, especially with the diversity of programs at the University, we have to constantly find ways to support each other.” The dental school operates year round, depends on faculty to practice what they teach and could easily earn multiples of their salaries, and our teaching program is built around a direct service to the public.

Initial Licensure

When Redig came to Pacific, the pass rate on the state boards was often about 60%. There were irregularities, such as the fact that candidates were not anonymous to examiners. In 1971, the deans of the then five California dental schools forced the creation of a “blue ribbon committee” to recommend changes. The nucleus of change started at the time but was accelerated with help from Christoffersen, who served on the Dental Board of California from 1993 to 2001. A succession of changes took place. The conduct of the board administered by the state was improved, reciprocity was enhanced and the Western Regional Examining Board was developed. Students were given specific preparation for boards as part of their instructional program. Today, the typical pass rate exceeds 90%.

And the Dugoni School of Dentistry is again leading the nation on initial licensure. Abelson, current associate dean for clinical affairs, explains how the new California portfolio licensure process works. “While they are students, candidates declare, perform and are evaluated on patient treatment in six disciplines. This care is provided in sequence as part of comprehensive patient care. Students are evaluated by two calibrated faculty examiners, who use state board standards. This is much more representative of how dentists will practice than any other current initial licensure system.” Candidates also have to present evidence (in their “portfolio”) of their ability to manage a balanced family of patients. The cost of the portfolio system to candidates is one-tenth of fees for other options, excluding patient procurement and travel for traditional state board exams.

Continuing the Journey

Redig started the dental school on a journey by making swift, necessary changes and by drawing our attention to the most important work to be done. He did not see all of his projects to completion; improvement is an ongoing process and many very talented people have joined and continue the effort.

In the late 1960s, the Commission on Dental Accreditation came to San Francisco with the very realistic possibility of closing the dental school down. Today, the Dugoni School of Dentistry is setting the standards by which all schools are judged. Comprehensive care, humanism, competency-based curricula, a physical facility that supports the education and patient care mission and balanced University relationships with stable and transparent financial arrangements have all been written into the accreditation standards. Pacific provided the first draft in every one of these areas thanks to Dr. Dale Redig.

David W. Chambers, PhD, is a professor of dental education and former academic dean at the Dugoni School of Dentistry, and is editor of the Journal of the American College of Dentists.

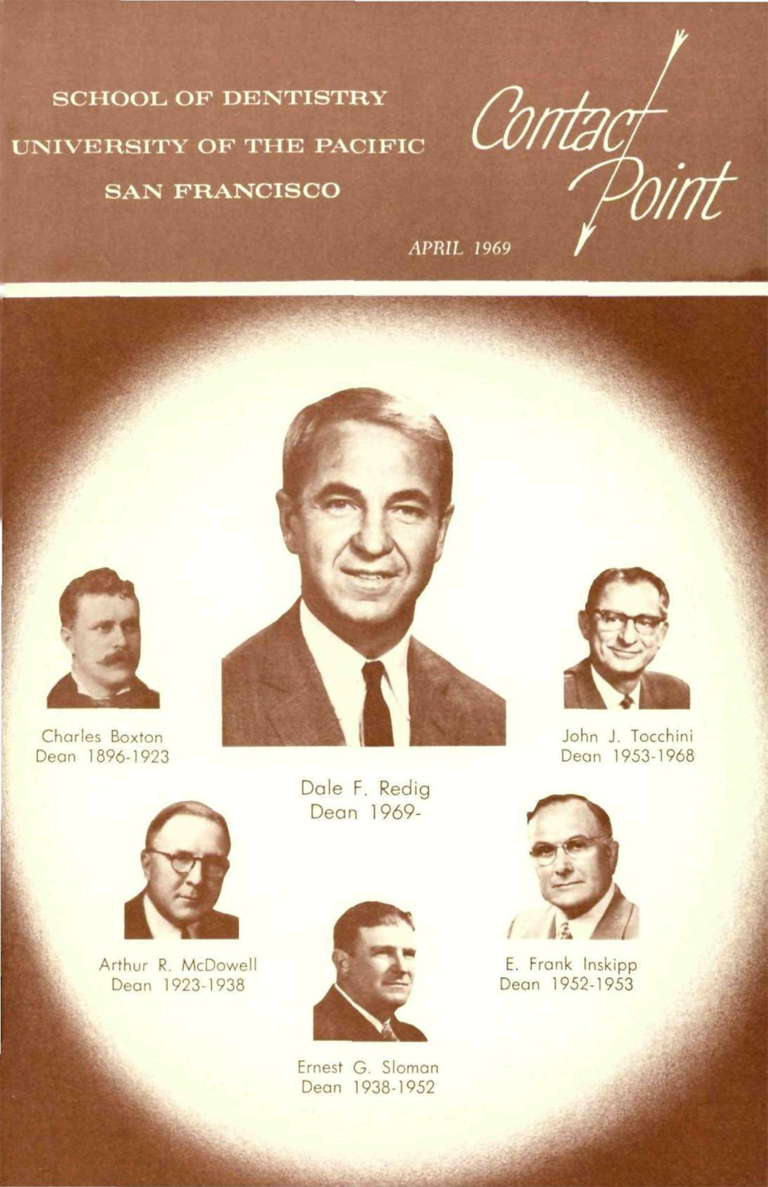

Dean and Mrs. Dale F. Redig and family from Contact Point in 1969: from left, daughter Catherine, son John, wife Diane, Dr. Redig and daughter Ann.

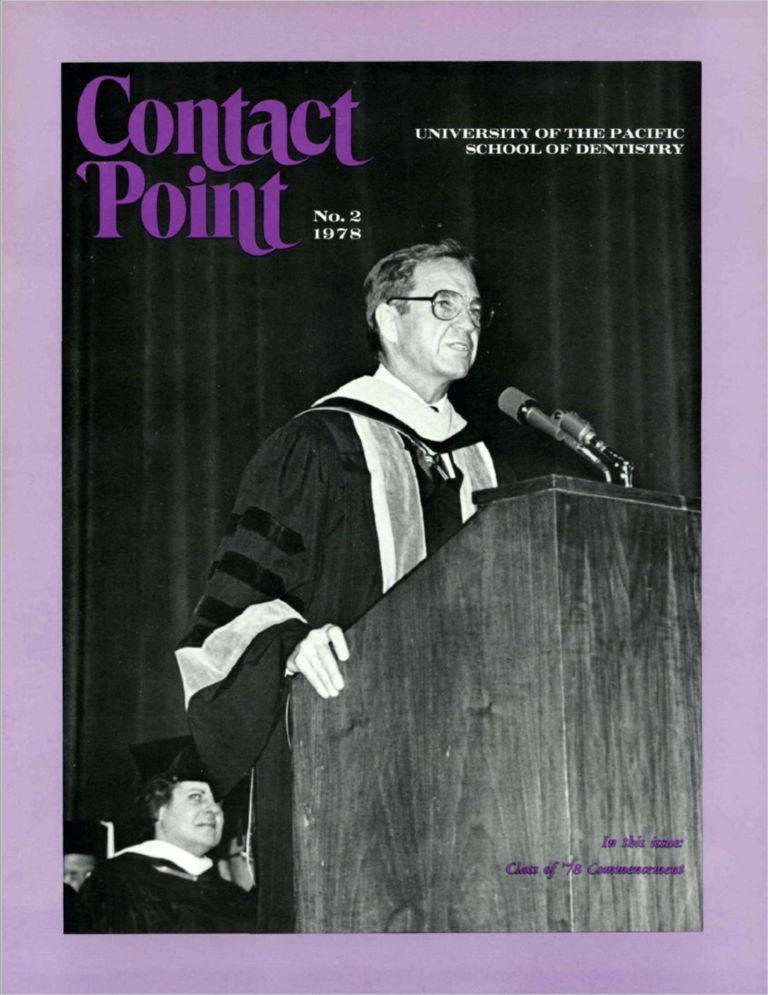

Dr. Redig addresses students’ wives.

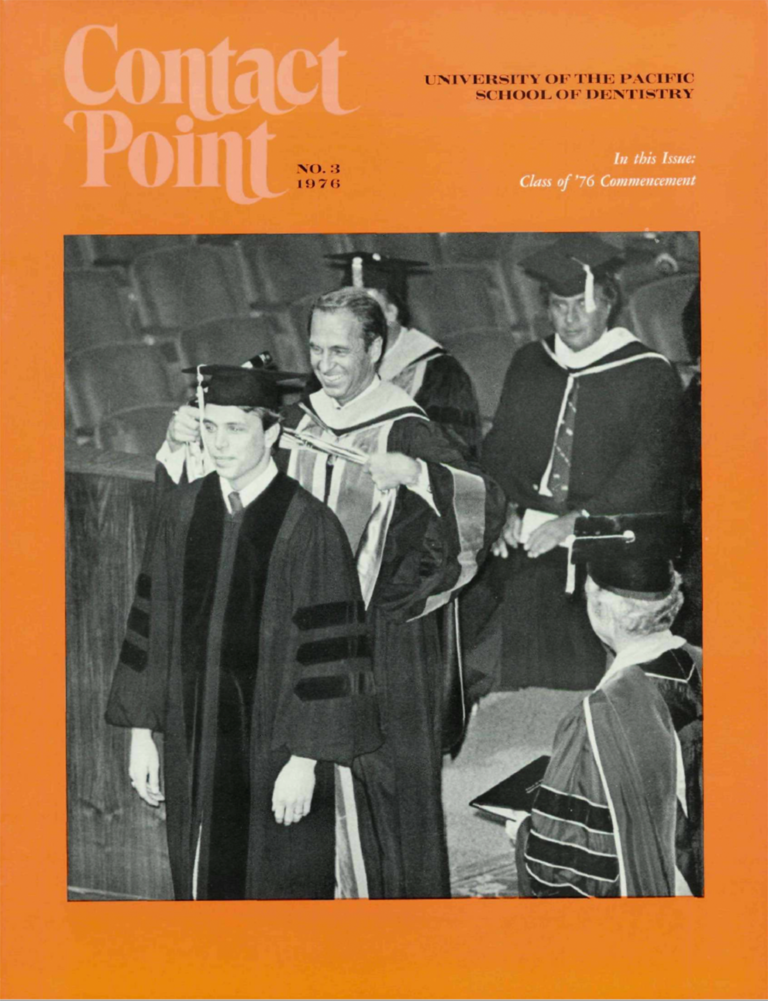

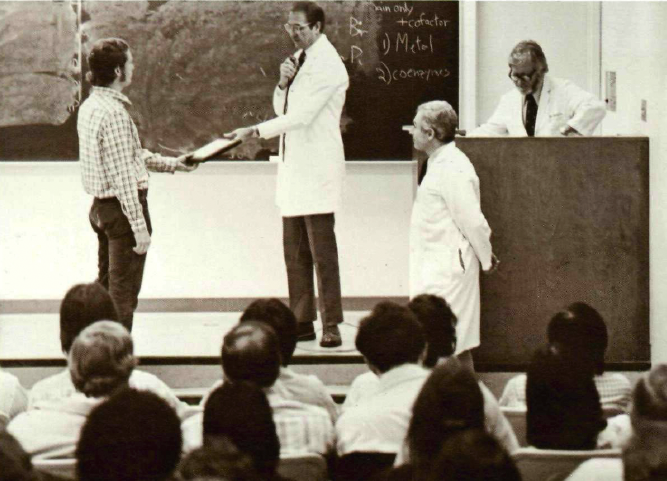

Dr. John Hendy ’77 accepts a plaque from Dean Redig for winning first place in Catagory II (Basic Science and Resesarch) at the ADA Annual Session for his table clinic. At right, are the late Drs. Armand Lugassy and John Corwin ’59.