Practicing Dentistry in Unusual Settings

By Kathleen A. Barrows

Working in a classic neighborhood dental practice isn’t for everyone. Some alumni, after years of practice, have tired of the long hours or daily routines. For others, the harsh economic realities of setting up a practice, especially in today’s high-rent urban areas, can be challenging. We interviewed three alumni of the Arthur A. Dugoni School of Dentistry who have found innovative ways and settings and, in some cases, even unusual patients on whom to use their dental skills.

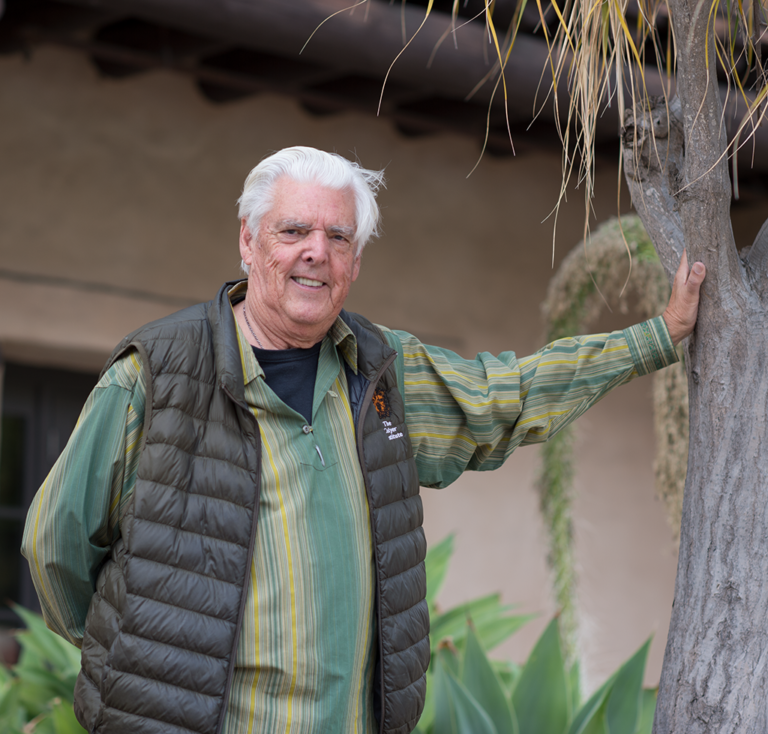

Dr. David Fagan ’66

We were lucky to catch up with Dr. David Fagan ’66, who was on his way to Canada to help provide a state-of-the-art, full metal crown restoration and treat exposed pulp tissue. In most dental practices treating exposed or bleeding pulp tissue is a fairly normal event. But Fagan’s patients are not exactly “normal.” This one was a walrus with a broken tusk. His other patients include cheetahs, monkeys, eagles, lions, pandas, gorillas and elephants.

Fagan had a short career as a chemical research engineer working with NASA before becoming a member of the last graduating class from the old College of Physicians and Surgeons (P&S) in San Francisco’s Mission District. During the 1960s and early 1970s, he established a multi-specialty, multi-location dental group practice offering 24-hour emergency, on-call service for everyone from the upscale hotel industry to the Haight-Ashbury street people.

His decision to change his patient population from “bipeds to quadrupeds” occurred when he took his daughter’s ailing horse to the School of Veterinary Medicine at University of California, Davis, to investigate what turned out to be a cracked patella. Fagan was asked, since he was a dentist, if he would take a look at another horse with a sinus problem, which he did. What resulted was a five-year relationship consulting in research, clinical care and lecturing with the university’s William R. Pritchard Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital, which was at the forefront of making dentistry a recognized sub-specialty of veterinary medicine. Ever since, he’s been applying his diagnostic, clinical and surgical skills to animals rather than people.

In those early days, Fagan admits “nobody recognized that animals had the same sort of range of oral and dental problems as humans; the general assumption was that some just had bad breath.” His first exotic animal surgery involved removing the four canine teeth, per health department orders, of a South American woolly monkey who had bitten a dinner guest at Juanita Musson’s legendary Galley Restaurant in Boyes Hot Springs, California.

After moving to San Diego in 1974 and working with Dr. Kurt Benirschke, then director of research for the San Diego Zoo, Fagan has gone on to become recognized internationally as a traveling dentist treating exotic animals around the world—from China to South America to Europe. His many accomplishments include developing a complete mobile dental unit that can be used anywhere, at any time, with any animal; discovering that there are no sensory nerves in elephant tusks; researching the relationship between diet and abnormalities in the dentition of cheetahs and elephants; and developing special instruments to perform endodontic therapy on large carnivores.

[pullquote]

His first exotic animal surgery involved removing the four canine teeth, per health department orders, of a South American woolly monkey who had bitten a dinner guest at Juanita Musson’s legendary Galley Restaurant in Boyes Hot Springs, California.

[/pullquote]

In 1981, he founded the non-profit Colyer Institute (www.colyerinstitute.org), a center for the study of oral disease and nutrition in exotic animals, named after the pioneering British dental surgeon Sir Frank Colyer and his brother, who were instrumental at the turn of the 19th century in making dentistry a recognized clinical sub-specialty of modern veterinary medicine.

Fagan has published an entertaining and informative book about his life and role in the development of modern veterinary dentistry (Dentist Goes Animal, available through Amazon). He aptly summarizes his story as “a lifetime of helping a host of very interesting exotic animals, both captive and free-ranging.”

Dr. Gregory Mar ’88

Dr. Gregory Mar ’88 describes his career as “atypical,” and indeed it is, considering that he’s a captain in the San Francisco Police Department. After completing dental school and an oral surgery fellowship, he practiced dentistry for three years, using his postgraduate training in oral and maxillofacial surgery for complex cases too difficult for the average dentist to handle. It was a conversation with a friend that inspired him to take a hiatus from dentistry and join the police department, where Mar had already volunteered as a reserve officer, assisting and supplementing the full-time police officers in a variety of departmental duties.

He was sworn in as a full-time officer in 1991 and three years later, after also completing a master’s degree in educational psychology, was recruited to join San Francisco’s Crime Scene Investigation (CSI) Unit. He has served on the unit for 14 years, rising from sergeant-inspector to the rank of captain, and only recently was transferred out when it became a civilian position. Mar jokes that his greatest claim to fame is being the only practicing police captain involved in two well-known TV shows—CSI and SVU (Special Victims Unit).

So how does a trained dentist use his skills on the job as a police officer? With his scientific background, Mar was a natural for analyzing fingerprints and detecting gunshot residue. He also serves as a forensic dental consultant to the San Francisco Medical Examiner. Close examination of the third molar, he explains, can determine whether an unidentified body is that of an adolescent or an adult.

He also is a specialist in bite mark analysis. Dogs’ teeth have particular features and the resulting bite marks can, in the absence of witnesses, be a major point of forensic interest in cases involving canines. Mar was involved in the investigations of two well-known San Francisco dog attacks—the 2001 case of Diane Whipple, the lacrosse player and coach who was killed in a San Francisco dog attack, and the death of a 12-year-old boy killed by two family pit bulls in the city’s Sunset District four years later.

Mar still maintains his dental license, using his practice to serve the community in yet another way, far from the world of policing. He works with disadvantaged populations in community dentistry, mainly doing pre-prosthetic surgery at San Mateo General Hospital, Oakland’s Highland Hospital and La Clinica de la Raza Community Clinic, in Oakland’s Fruitvale district, with dental school faculty member, Dr. Eugene LaBarre.

[pullquote]So how does a trained dentist use his skills on the job as a police officer? With his scientific background, Mar was a natural for analyzing fingerprints and detecting gunshot residue.[/pullquote]

Mar recently team-taught a continuing education course at the dental school, Forensic Odontology: Is it CSI Dentistry?, where he explained the work of forensic dentists in the criminal justice system.

“Law enforcement is my full-time job,” says Mar, and “dentistry is a hobby.” His police career has allowed him to break out of what he calls the “monotony” of dentistry. “It’s been a wild ride,” he admits. “It’s unique to be a part of the Dugoni School family and not be taking the traditional path.”

Dr. Nataly Yoncee ’17

As a member of the First Dental Battalion, serving the United States Marines, Dr. Yoncee practices in a dental office on a military base—Camp Pendleton in San Diego. Though an excellent student in high school, she realized upon graduating that she wasn’t prepared for college nor drawn to any profession. So at the age of 17, she enlisted in the United States Navy. Yoncee served active duty for four years, working in supply and stationed on both a naval ship and in a helicopter squadron. Today, she owes her dental career completely to the military. “The Navy changed my life,” she says.

Yoncee had entertained the idea of becoming a dental technician, but it was a chance encounter with a dental officer, while she was a patient in a dental van that services Navy personnel when ships are in port, that gave her the idea of becoming a dentist and using the Health Professions Scholarship Program (HPSP). “There’s no way I would have gone to dental school without it,” she admits. After her four years of service, she used the post-9/11 GI bill to get her bachelor’s degree at University of Callifornia, Berkeley, and went on to the Dugoni School of Dentistry with a Health Professions Scholarship.

Currently, she’s a resident in the Advanced Education in General Dentistry program at Camp Pendleton, serving the active-duty Marines on the base. “It’s great exposure to all facets of dentistry,” she says, as she learns how to treat a variety of dental issues, from check-ups to pre-maxillary fractures. She credits her experiences as a 24-hour, on-call emergency dentist—dealing with lip contusions and lacerations—with helping her feel more comfortable in trauma situations.

[pullquote]Nataly owes her dental career completely to the military. “The Navy changed my life.”[/pullquote]

Because she’s a military officer first and not only a dentist, Yoncee has had to do military training that most dentists can never imagine. She recently completed a casualty care course to prepare her for combat situations when she is assigned as a triage officer on a medical team for dealing with wounded soldiers in combat situations. The simulated mass casualty scenarios included wearing gasmasks for use in chemical warfare, dealing with injuries from IED bombs, pulling wounded soldiers back to safe areas and even firing back at the enemy.

Yoncee realizes that the military can take a toll on family life. So, she may later retire from the military and start her own practice as she hopes to have children someday. But before she does, she would like to serve on a Naval ship. Her military service has instilled discipline and self-confidence, and at age 30 she enjoys serving as a mentor to young corpsmen and corpswomen who know she’s been in their situation.

Yoncee volunteered at last year’s dental school Veterans’ Day event, offering free dental check-ups to veterans. “It’s odd to think of myself as a veteran,” she says, “but there’s nothing I’d rather be doing than defending my country.” She urges people not to forget “the people out there standing watch.”

Some of these alumni have searched out non-traditional settings to practice their art, while others have discovered an unexpected passion leading them to re-define the form of their dentistry. All are contributing invaluable services to their communities and patients, be they human or animal.

Kathleen A. Barrows, an East Bay freelance writer, is a contributor to Contact Point.

Dr. David Fagan ’66

Dr. Gregory Mar ’88

Dr. Nataly Yoncee ’17