By Dan Soine and Dr. David W. Chambers

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused dental schools across America to reimagine many aspects of their programs, including clinical operations, infection control, educational technology—and one of the first major milestones for dentists: initial licensure exams.

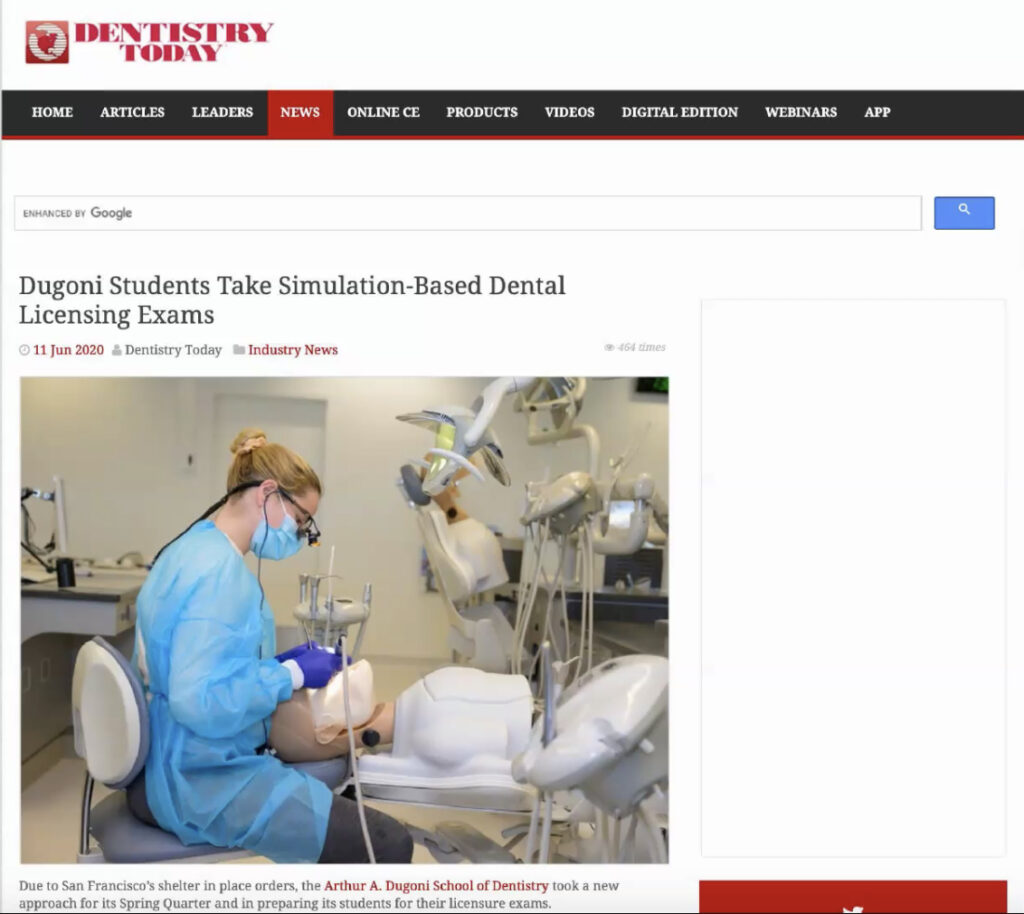

Due to the shelter-in-place orders in the San Francisco Bay Area, the Arthur A. Dugoni School of Dentistry needed to take a new approach for its spring quarter and to determine how it would prepare graduating students for these crucial exams. Routine dental care was not allowed during shelter-in-place, which meant that no patients could be scheduled and graduating students would not be able to treat their patients for the performance part of initial licensure examinations.

Dugoni School leadership worked closely with the Western Regional Examining Board (WREB) and the Dental Board of California to come up with options for the licensure exams. WREB is one of the five examination agencies for dentists and dental hygienists in the United States.

Dental degrees are granted by schools, based on a student’s competency of being able to perform the skills expected of beginning practitioners, understand the scientific foundation for oral health care and exhibit appropriate professional values. All U.S. dental schools are accredited by the Commission on Dental Accreditation and must provide evidence that their curricula prepare students to meet competency for beginning practice and that schools have evaluation systems in place to ensure this.

Licensure is a commercial qualification regulated by individual states to provide standards of protection to consumers who cannot evaluate the quality of the work being performed. Financial advisors, building contractors, real estate agents and others are licensed. A branch of the state government, such as the Department of Consumer Affairs in California, sets regulations consistent with state laws, manages enrollment of licensees and monitors and disciplines them as appropriate. Members of licensing boards all serve as public members regardless of their professional qualifications.

The Arthur A. Dugoni School of Dentistry and other California dental schools used a simulation-based exam for the first time this spring. The manikin-based exam had the additional advantage of occurring during one weekend—June 6 to 8—at the Dugoni School of Dentistry campus in San Francisco. Typically, the patient-based exam is scheduled over two weekends with half the graduating class taking the exam one weekend and the other half taking it the subsequent weekend.

The Dugoni School of Dentistry’s building operations and clinical operations teams worked diligently to prepare the dental clinics for this new approach. The school turned 72 of its dental clinic operatories on its third floor into simulation stations by removing the headrests and installing dental manikins to serve as patient simulators. This engineered solution allowed students and test takers to authentically simulate the patient care experience using exactly the same instrumentation and ergonomics used for direct patient care. Along with a host of safety measures for screening,

advocacy supported licensure for the graduating students. Equally important, this advocacy allowed for these dentists to enter practice and begin addressing the pent-up need for oral health care in our communities after a prolonged sheltering in place. The Dental Board of California and California Department of Consumer Affairs ultimately approved the non-patient-based exam and allowed it to move forward.

At one time in history, each state constructed and administered its own licensure test. But recent years have seen major shifts in this model. Currently, there are five regional testing agencies and a test is being developed under the

leadership of the American Dental Association (ADA). There is no national standard. Only one state, Louisiana, administers its own performance examination. All states have unique standards for licensure that recognize results of some testing agencies but not others. For example, Delaware does not recognize the results of any examining agency and requires three years of practice in another state or completion of a general practice residency or specialty program. The rules change constantly, and other states that recognized the traditional WREB examination process may not recognize the manikin model completed by Dugoni School of Dentistry students.

States have delegated performance testing to various examining agencies. These regional agencies are commercial organizations that charge candidates for examinations and use volunteer practicing dentists as graders. Most states require an additional written test covering the state’s practice act. State licensing boards also require that candidates have passed the nationally standardized and validated National Board examinations that cover competency in the foundational knowledge of oral health care. They also require graduation from a U.S. accredited dental school and a verified criminal background check. States have various systems of granting licensure by reciprocity, based on successful practice in other states for certain periods of time. Of the many requirements for licensure to practice dentistry, state boards do not actually test or gather first-hand data on the qualifications of dentists, other than perhaps knowledge of the practice act. All of this is delegated to various entities, particularly the dental schools and commercial testing agencies.

Feedback about the simulated exam from students and examiners alike has been positive. The school’s clinical leadership had a debriefing with the WREB chief examiner who was very complimentary about how well prepared the students were for this new exam format.

“It was definitely nerve-wracking being one of the first classes to take the manikin-based exam, but the school did a great job of preparing us the week beforehand,” said Dr. Leah Life ’20. “I’m grateful we had the opportunity to take it so soon after the Dental Board of California approved the manikin-based exam. I think it was a great test of our abilities and our class did well.”

A performance-based examination as a requirement for licensure in the health professions began in the early 1900s. It has been discontinued by all professions except dentistry. When dental schools were for-profit operations with very little clinical experience, independent testing of the graduate made eminent sense. William Gies, in his landmark 1926 study of education, thought the practice had served its usefulness and was creating an unnecessary tangle of political and regulatory requirements. The period between 1940 and 1960 saw the publication of papers and reports by groups representing both education and boards working together on standards for education and practice. Former Dean Dale Redig campaigned effectively for making the tests anonymous. Dean Emeritus Arthur A. Dugoni had long advocated for change, including licensure upon graduation. Dr. David W. Chambers was an early advocate for portfolio licensure where candidates submit documentation showing successful completion of representative procedures performed to board standards while in dental school.

Dr. Letitia Edwards ’20 commented, “Being the first class in the nation to take an entirely manikin-based licensure examination felt like history in the making. Organized dentistry has been advocating for years to remove the patient-based components of the licensing exams in lieu of a manikin portion, and we’ve finally done it! I hope that this will continue for years to come. I can’t thank the Dugoni School family, WREB examiners and staff members enough for helping us in our journey to become licensed dentists. Everyone truly came together to ensure that the exam ran smoothly, without any hiccups, and that we could perform our best even under these turbulent circumstances.”

The issues, of course, are validity and portability. Validity is a technical term for the degree to which scores on an examination provide robust predictions regarding future performance. In the case of licensure, the validity question is whether those with scores above a certain cut score on a licensure exam serve the public’s oral healthcare needs while those below the cut score are a danger to the public. There are no published data in the peer-reviewed literature that supports this claim for past examinations’ procedures or for any of the alternatives being considered as replacements.

Portability is the matter of whether qualifications for licensure in one state will be recognized in others. Historically, this has presented some challenges to increasingly mobile professionals. The regulations are not consistent across the country and change frequently. Some state boards have already discussed whether they will recognize licensure based on the ADA’s new protocols or on manikin tests.

Each year in California, approximately 80 dentists have their licenses disciplined by the state board. That is roughly equivalent in number to half of each year’s Dugoni School of Dentistry graduating class, although Pacific graduates are almost entirely absent from this group and half of dentists practicing in California did not attend dental school in the state. These records are available online. The leading causes are incomplete records, overtreatment, overbilling, insurance fraud and a range of personal challenges, such as improperly dispensing or using drugs, DUIs, sex with patients and even crimes such as assault and impersonating a state board investigator. Only one case has been found in recent years of a dentist losing his license for a technical procedure tested on licensure exams. The average age of a dentist with a disciplined dental license is 57, the same age for physicians.

The schools, the ADA and student groups such as the American Student Dental Association and the Student Professionalism and Ethics Society have long called for an end to performance-based testing for licensure. The arguments have centered on lack of validity evidence, ethical abuses of patients engendered by the process and the substantial financial burden on graduates who are required to take the test a second time. Repeat testing, which results in a virtual 100% pass rate for candidates, can lead to lost associateship opportunities, missed participation in the military and other loan forgiveness programs and direct costs.

The response over the past half century has been a gradual constricting of the domain of performance testing. Gold foil is gone; periodontal treatment is scaled back; denture work and

crown fabrication are going to the lab. Currently the ADA is leading a consortium in developing and validating a single test to be accepted, it is hoped, by all states in order to ensure professional movement. Known as the Dental Licensure Objective Structured Clinical Examination (DLOSCE), the platform is based on station challenges with radiographs, three-dimensional models and patient descriptions that candidates rotate through and mark with multiple choice answers like the National Boards. This format offers an advantage in providing each candidate with exactly the same challenge that other candidates face, evaluated by means of objective standards. The focus is clinical judgment. In states such as Oregon, DLOSCE was used instead of the patient-based or manikin-based test this spring.

“I’m so proud of the entire family here at the Dugoni School of Dentistry and all of our partners, especially the California Dental Association, who helped make this simulation-based licensure exam a reality,” said Dean Nader A. Nadershahi ’94. “This creative approach ensured that our graduating students could finish up their programs and pass this key milestone before moving to the next phase of their career, instead of having to wait many more months or longer to take the WREB exam. While the pandemic has caused much disruption, it has also allowed us to pursue innovative approaches to dental education and licensure. I am confident that these graduates will help shape an even stronger future for our great profession.”