Passion for Pacific: Alumni Give Back

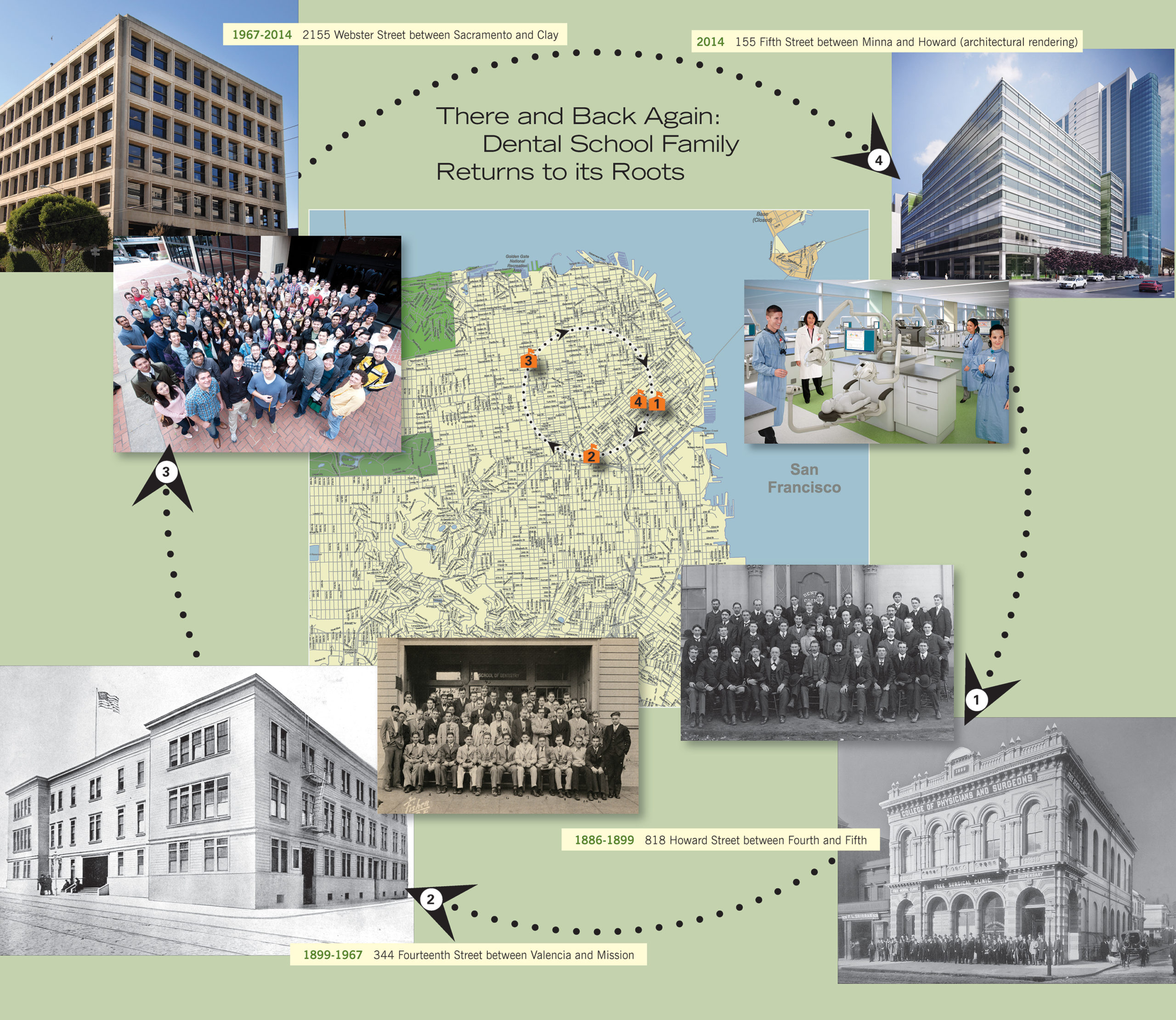

Such rough conditions were very real at the old dental school, the College of Physicians and Surgeons, where in the early 1960s four students—Paul Senise, Ernest Giachetti, Kenneth Frangadakis and Morel Fidler—became roommates and forged a deep friendship that still continues after more than 50 years.