By Dorothy Dechant

Former University Provost Phil Gilbertson writes in the opening line of his recent book, Pacific on the Rise: the Story of California’s First University, “It all started with the Gold Rush of ’49.” By promoting education, the Methodist founders of the University had hoped to spread “civilizing” influences, and counter the gold-discovery-induced “unregulated greed and violence” to which San Francisco and surrounding areas had succumbed. Over time, as gold diminished and that frenzy subsided, Pacific established positive relations with the Gold Country, nurturing and promoting preservation of the town of Columbia, to recognize and honor its role in the rich history of California.

In March 1850, not far from Pine Log, California, transient prospectors discovered gold. Originally named Hildreth’s Diggings, the site quickly evolved from a mining camp to the bustling, internationally diverse community of Columbia. Businesses, social organizations, places of worship, theaters, restaurants, hotels, schools, newspapers and cemeteries were established, along with the requisite saloons/gambling houses and banks and renowned European chefs, doctors, teachers, lawyers and barbers (versed in pulling teeth) were among the varied professionals attracted to this prosperous, self-sustaining boomtown. Incorporated on one square mile, at its peak the town’s population numbered around 6,000 permanent residents.

Ties with San Francisco were strong, as many merchants moved their businesses from the City to Columbia. During the 1850s, Columbia’s citizens were enjoying and exchanging considerable wealth. Claims were producing a lucrative one ounce of gold per day, and yielding a weekly “take” worth $100,000. By 1857 a number of towns in California’s Mother Lode were in decline, but Columbia’s 4,500 miners continued to extract up to $17,000 in gold per week, and earn $8 to $10 daily.

After the Boom Comes the Bust

By the late 1860s, the town’s population had dwindled as the abundance of gold diminished and families moved on to stake more profitable claims elsewhere. When residents departed, their vacated buildings were torn down and the plots mined. Columbia’s overall valuation dropped from near “$1 million in the late 1850s to $150,000 in 1868.” Gold no longer fueled the economy, but the remaining 500 residents adapted to the changes by working in the local marble quarries, for the water company, at farming or ranching or as merchants providing supplies to other mining camps in the Sierra foothills.

[pullquote]Pulling teeth was about all dentists did in the 1850s.[/pullquote]

P&S Dentist Helps Revive Historic Columbia

Though its wealth and resources declined, and buildings deteriorated, Columbia was never entirely abandoned. Fond memories of the town as the “Gem of the Southern Mines,” so nicknamed for its wealth, diversity and ambience, still lingered in the stories of resident “old timers.” Over the years, the town’s character had retained much of its original feel as when miners and merchants roamed the streets.

Enthusiasm for recreating the excitement of California’s colorful gold rush history by restoring Columbia began to grow. Local residents suggested that Columbia be included in the new California State Parks System, but efforts in the 1920s and 1930s to raise enough funding for building restoration failed.

As new residents of the town in 1940, Dr. James McConnell ’24, a dental graduate of San Francisco’s College of Physicians and Surgeons, and his wife were instrumental in raising $50,000 in matching funds to finally secure Columbia a place in the parks system. In 1945, McConnell, then chairman of the Columbia State Park Committee, was present when California Governor Earl Warren signed the bill. An inspired supporter of the project, the governor imagined Columbia becoming “the Williamsburg of the West.” Based on old plans and photographs, new replica buildings were constructed, and those historic buildings still standing were restored.

Pacific Summer Theatre at Columbia

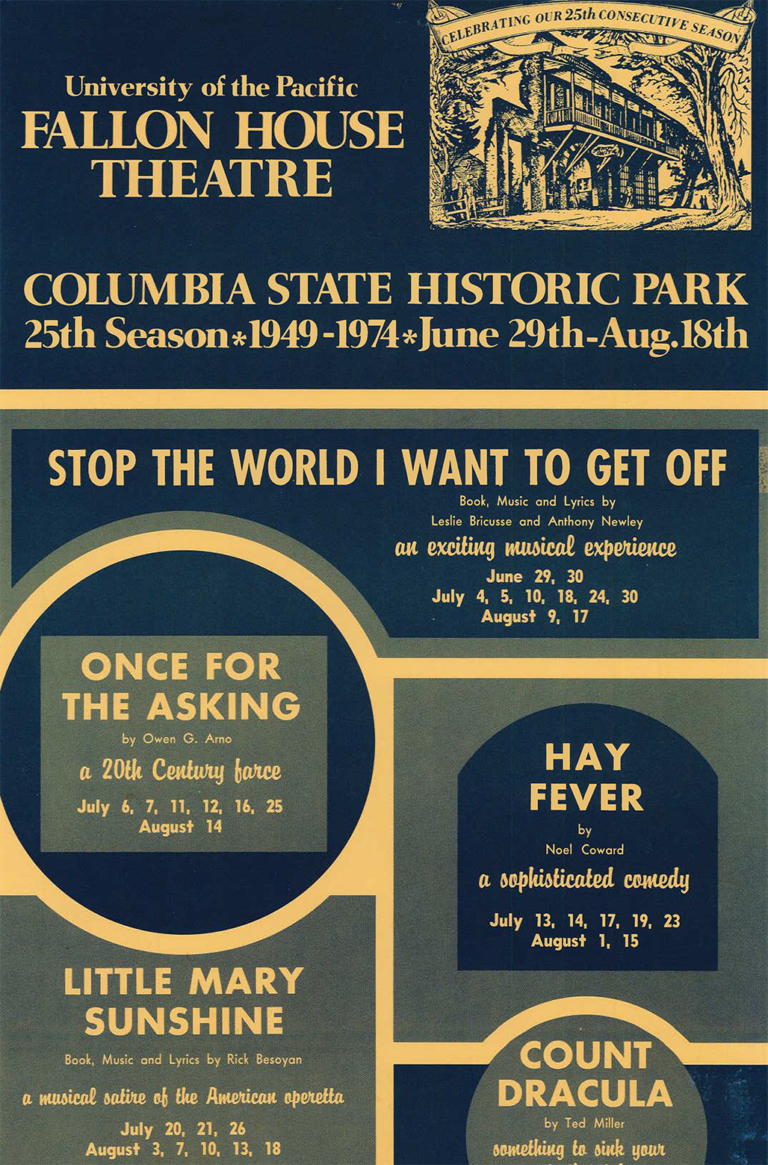

For 40 years, from 1949 to 1989, University of the Pacific’s drama students inhabited Columbia when the Fallon House Hotel and, later, Eagle Cottage served as their residence during the school’s summer Fallon House Theatre repertory. Throughout a 95-year period, Fallon House Hotel had changed hands repeatedly, was burned and rebuilt after three separate fires and underwent a number of remodels, with the theatre added on in 1885. In 1944, Dr. Robert Burns, then president of the University, had purchased the hotel and later, in 1947, sold it to the State of California for $1. Soon after, the State and the College of the Pacific collaborated to support the Fallon House Theatre and make Columbia a popular stopover for performance enthusiasts.

1870s Operatory Becomes Columbia’s Dentist Office Exhibit

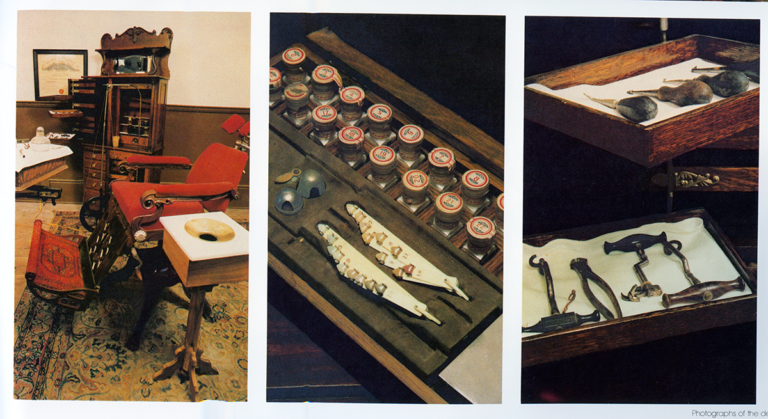

In July 1978, the Pacific-Columbia connection grew even stronger when artifacts from the dental office of Dr. Paul F. Sikora, P&S Class of 1908, were donated by his son, Columbia dentist, Dr. Paul J. Sikora, to create an 1870s-era operatory for the park’s new Dentist Office display. Following a luncheon held at the University’s cottage (formerly owned by President Burns), outgoing dean of the dental school, Dr. Dale Redig, attended the opening celebration along with more than 100 alumni, students, staff, faculty and friends. The display included a 1850s case of ivory handled dental instruments and tooth keys dating back to the Revolutionary War period on loan from the school’s A.W. Ward Museum collection.

After its debut, local Sonora and Columbia dentists were enlisted as honorary curators to help maintain the Dentist Office exhibit. One such curator, Dr. Matthew Cummings, also entertained visitors as a “living history performer,” portraying Dr. Malcolm McCleod Moore, Columbia’s first tooth extractor. He would dress the part, wearing a top hat, vest and gold chain with pocket watch, to impersonate a mid-19th century dentist, and display a jar of teeth, explaining that, “Pulling teeth was about all dentists did in the 1850s.”

The Dentist Office Today

Today, members of the Ward Museum Committee travel to Columbia periodically to dust the artifacts, check the lighting and make upgrades to the sound system. On busy days, a steady stream of tourists arrives at the Dentist Office viewing window, one of the park’s most popular exhibits. Many are captivated and some distressed by the array of mid-1800s elegant but scary-looking instruments. The reenacted dialogue between a gold miner and a dentist reminds visitors how lucky they are to enjoy 21st century dentistry!

[pullquote]The reenacted dialogue between a gold miner and a dentist reminds visitors how lucky they are to enjoy 21st century dentistry![/pullquote]

Dorothy Dechant, PhD, is an adjunct assistant professor in Biomedical Sciences and curator of the Dugoni School of Dentistry’s Institute of Dental History and Craniofacial Study.

Listen in on a Gold Rush-era dentist appointment in this reenactment.

Poster courtesy of Theatre Arts Department, University of the Pacific