by Dr. Eric Curtis

In many dental schools, the incoming class of students traditionally gathers for an official greeting from the dean. And in many institutions, this greeting usually included, of all things, a threat. My father, Dr. Kay D. Curtis, who graduated from a different dental school, clearly remembers that inaugural lecture. “Look to your right,” his dean instructed, “and look to your left. By the end of the year, one of you won’t be here.”

Dr. Nava Fathi ’95, a member of University of the Pacific’s Board of Regents, recalls a very different reception at Pacific. “Dear Dr. Dugoni,” she writes, “Twenty-nine years ago, the first day of school, you cast your spell on my classmates and me with your empowering welcome speech: ‘Look to your right, look to your left and you will see your best friends and family for life.’”

Dr. Arthur A. Dugoni ’48 had a way of turning problems into solutions and crises into breakthroughs. He had a gift for spinning, as Fathi’s recollection implies, past threats into future blessings. Under his jurisdiction, dental education would no longer be a zero-sum game, but a big, welcoming tent, and its participants, instead of competitors, partners in success.

And that’s exactly what a leader does. A manager organizes people’s progress—the work of becoming a dentist, say, or holding down a faculty position or taking on a volunteer assignment—into intelligible and reasonable steps, explaining how to take those steps, and even why you should. A leader, on the other hand, makes you want to reach your potential. In Dugoni’s case, any number of students, instructors, administrators, colleagues, employees, alumni, family, friends, acquaintances, dentists all over the planet and folks he might meet in a hallway or on the stairs somewhere—want to go forward. A leader skillfully aligns your interests and impulses with something bigger than yourself, so that, finally, you are lifted by something more than mere pride of progress. A leader propels you toward a palpable sense of destiny.

To this end, leaders may harness a variety of qualities. In assessing potential executives, investor Warren Buffet reportedly looks for three virtues—intelligence, initiative and integrity. The Marine Corps identifies 14 essential leadership traits, including dependability, decisiveness, tact, unselfishness and loyalty. Dugoni likely knew all that. “He was a student of leadership,” says Dr. David Nielsen ’67, former associate dean and former executive director of the Alumni Association. “He read every book he could find on leadership, attended lectures and corresponded with many great leaders in all areas.” Dugoni’s own governing values, products of both scholarship and experience, might be divided into five broad categories: vision, generosity, example, energy and optimism.

“When I think of Art Dugoni, I think of the man who had the charisma of a politician, the good looks of a movie star and the savvy of a CEO of a Fortune 500 company. But that’s just what was on the outside. People gravitated to Art. They worked for him. They embraced his vision— because of what was in the inside.”

U.S. Congresswoman Jackie Speier

U.S. Congresswoman Jackie Speier, who represents California’s 14th congressional district, says, speaking at Dugoni’s virtual Celebration of Life on December 12, 2020, “When I think of Art Dugoni, I think of the man who had the charisma of a politician, the good looks of a movie star and the savvy of a CEO of a Fortune 500 company. But that’s just what was on the outside. People gravitated to Art. They worked for him. They embraced his vision—because of what was in the inside.”

People also embraced Dugoni’s vision because it was remarkably consistent and easily grasped. He established his focus early, balancing imagination with practicality, and he never wavered. As dean, he would develop Pacific into the finest dental school in the world. He would make its students, faculty, staff and alumni deeply proud of their program. He would develop, foster, encourage and endorse good ideas, whether modest or bold— graduate programs in orthodontics, general dentistry (AEGD) and oral and maxillofacial surgery; an International Dental Studies (IDS) program, a student housing facility; a state-of-theart preclinical laboratory; a student White Coat Ceremony; a baccalaureate dental hygiene curriculum; a Special Needs Clinic; an annual open house called Pacific Pride Day (now called Dugoni Discovery Day)—with discernment and a refreshing splash of camaraderie.

He would accomplish these good ideas with a combination of discipline, efficiency and human warmth. While willing to entertain a certain level of experimentation, he would ultimately execute them with precision, bringing to his table of projects the fruits of voluminous preparation, analysis and research. And he would advertise them relentlessly.

Dugoni was fond of communicating with slogans, pithy catchphrases that people would remember, relate to and repeat. He pushed for the improvement of physical facilities and patient care by calling for Pacific to become the “Ritz-Carlton” of dental schools. He pressed students, faculty and staff to surprise people with excellent service, exclaiming, “Knock their socks off!” He often called attention to the “Three Bs” of success, which eventually became 10: be there, be there on time, be prepared, be involved, be disciplined, be balanced, be kind, be generous, be happy and be alive.

Dugoni received the 2009 William J. Gies Award, presented by the ADEA Gies Foundation, for Outstanding Achievement — Dental Educator, in support of global oral health and oral health education.

Dugoni refined and personalized his vision of “humanism,” the doctrine of treating students with tolerance and dignity, encouraging them to hone not just technical competence but also to develop their full potential as human beings. As University Provost Emeritus Phil Gilbertson observes, “Under Art’s vision and leadership, the Arthur A. Dugoni School of Dentistry has stood out as the most admired dental school in the country, noted for excellence in all arenas of dental education and uniquely shown as a beacon for the powerful role of character building, to prepare professionals to be leaders in their field.”

While humanism seems, in retrospect, natural and inevitable, it began as a concept advocated by Dean Dale Redig, Dugoni’s immediate predecessor, to a behavior modeled by key faculty, among them Drs. Leroy Cagnone, Bob Christoffersen ’67, David Chambers, Ron Borer, Rollie Smith and Eddie Hayashida, to a belief system embraced throughout the school, to, finally, the assumption it is today. To drive the point home, Dugoni produced an aphorism heard—and ultimately absorbed—in the corridors of dental education around the world: “At Pacific we grow people, and along the way they become doctors.”

Art Dugoni’s Generosity

No leader can demand change without bringing a great deal of self-confidence to the task, but Dugoni successfully tempered his ego with great generosity of spirit. Pacific Provost and Executive Vice President of Academic Affairs Maria Pallavicini says, “I remember so many things about Art—his generosity, his passion, his integrity, and most importantly, how much he cared about each individual. Art was very generous with his time and with his ideas. He played a key role in recruiting every senior administrator at our University.”

Dugoni’s generosity also manifested itself in humility. Even as the man in charge, he accepted correction. “One time I told him I didn’t think the tone he was using in a letter would have the effect he hoped for,” Alumni Association Director Joanne Fox remembers. “He edited the letter.”

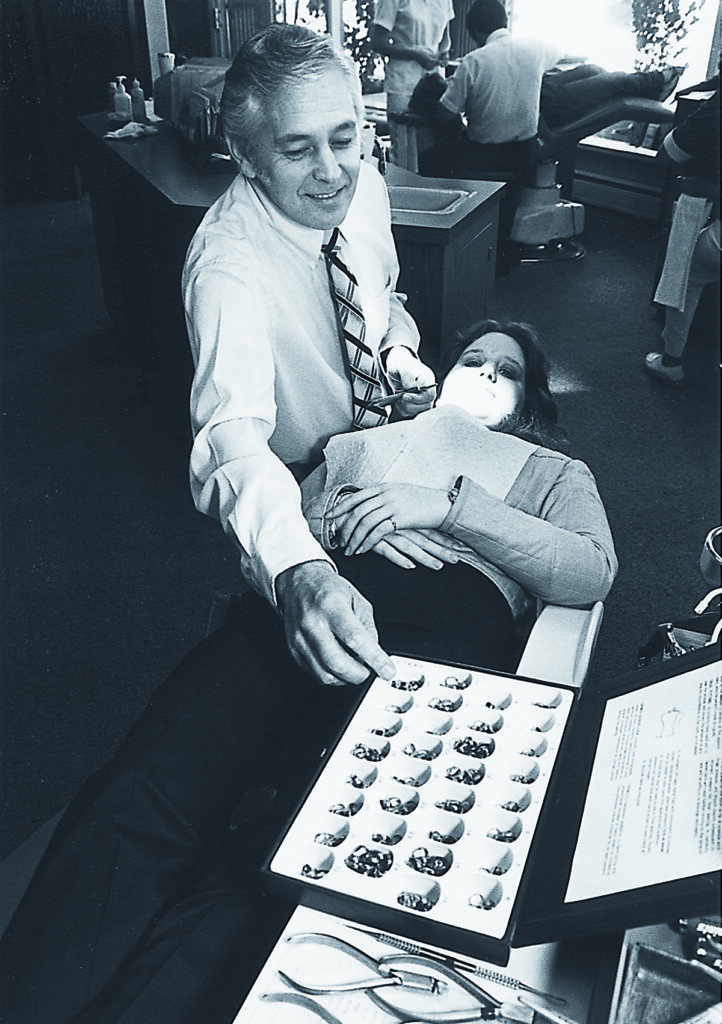

Dr. Ron Borer, former associate dean of clinical affairs, who helped pioneer the student clinic group practice model in the 1970s, marvels at Dugoni’s confidence in delegation. Instead of barking orders, he remembers, “Art would come down and ask me how I was going to do things.”

Famously supportive, Dugoni remained nonetheless careful in dispensing advice, leading by suggestion rather than judgment. Former American Dental Education Association President and CEO Richard Valachovic says, “Art Dugoni was a venerated mentor to deans, faculty and students throughout the United States, and beyond. He would tell us on many occasions, ‘A mentor doesn’t tell you what to think; a mentor helps you understand how to think.’” Yet Dugoni’s counsel was no less joyous for being discreet. “I learned from him how to be a better provost, a better leader, a better educator, a better person,” Gilbertson says. “His modeling for us was smart, ambitious, caring, loyal and generous.” Many remember Dugoni’s compassion. Others describe his empathy, and still others his patience. His correspondence was vast. His attentiveness was legendary. “Art went beyond being a friend,” Nielsen says. “He was respectful of others, and he had a huge ability to listen.”

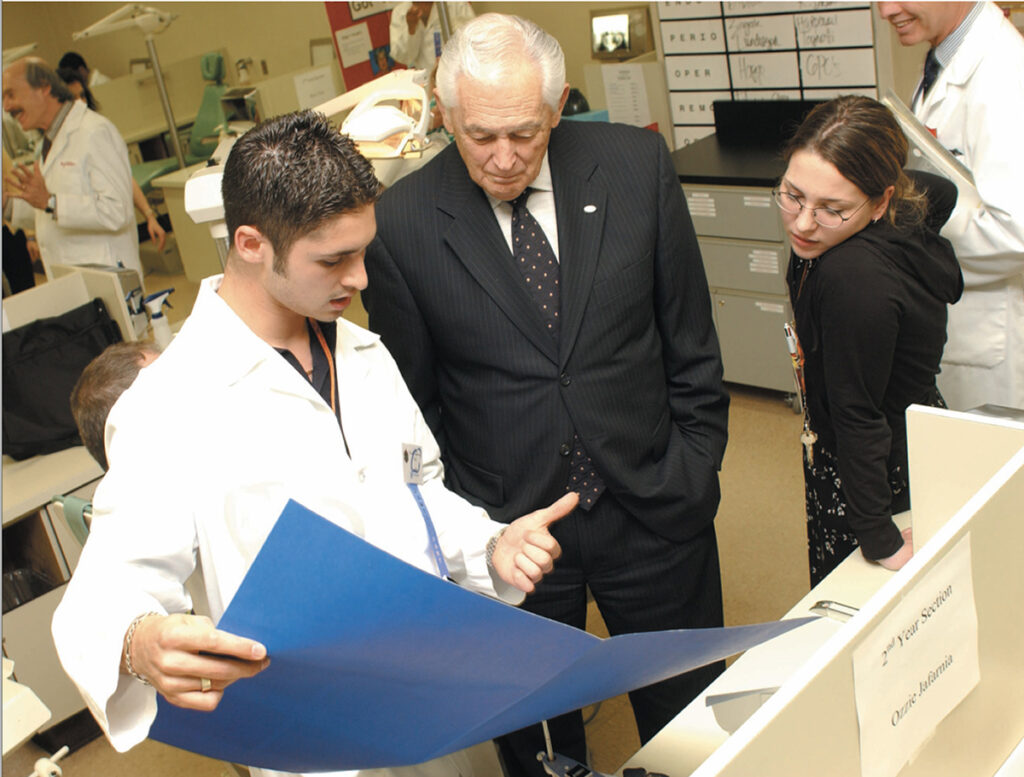

Dr. Bradford Smith ’86, dean of Midwestern University College of Dental Medicine-Arizona, recalls that Dugoni’s consideration always felt personal. “One trait that really always stuck with me was his ability to focus on an individual,” he says. “I don’t think I ever saw him get anxious or in a hurry when someone was talking to him. He always made others feel important, no matter what their stature in life.”

“Art Dugoni was a venerated mentor to deans, faculty and students throughout the United States, and beyond. He would tell us on many occasions, ‘A mentor doesn’t tell you what to think; a mentor helps you understand how to think.’”

Dr. Richard Valachovic

Former ADEA President and CEO

Grandson Dr. Brian Dugoni ’08, ’10 Ortho, says,” My grandfather, as we all know, had this charm about him. When he talked to you, you felt like you were the most important person in the room.”

Dugoni’s attention, while liberal, was also strategic. People could approach him with “the craziest ideas,” Nielsen remembers. “Art would listen to the whole story, ask some questions, and say, ‘Great idea. Let’s try it.’ Or, ‘Have you thought about this or that?’ Or, ‘Why don’t you run it by a couple more people and then come back to me, and we will discuss it some more.’ You would go away with a plan that was probably not what you started out with at all, but you would go away thinking that Art thought it was a great idea and we are going to try it out.”

Dr. David Chambers, former associate dean for academic affairs, sees in Dugoni’s forbearance a means of persuasion. “Art listened to you,” he says, “until you agreed with him.” Nielsen detects in such encounters a nurturing moment: “Art always brought out the best in every person he met.”

Art Dugoni’s Example

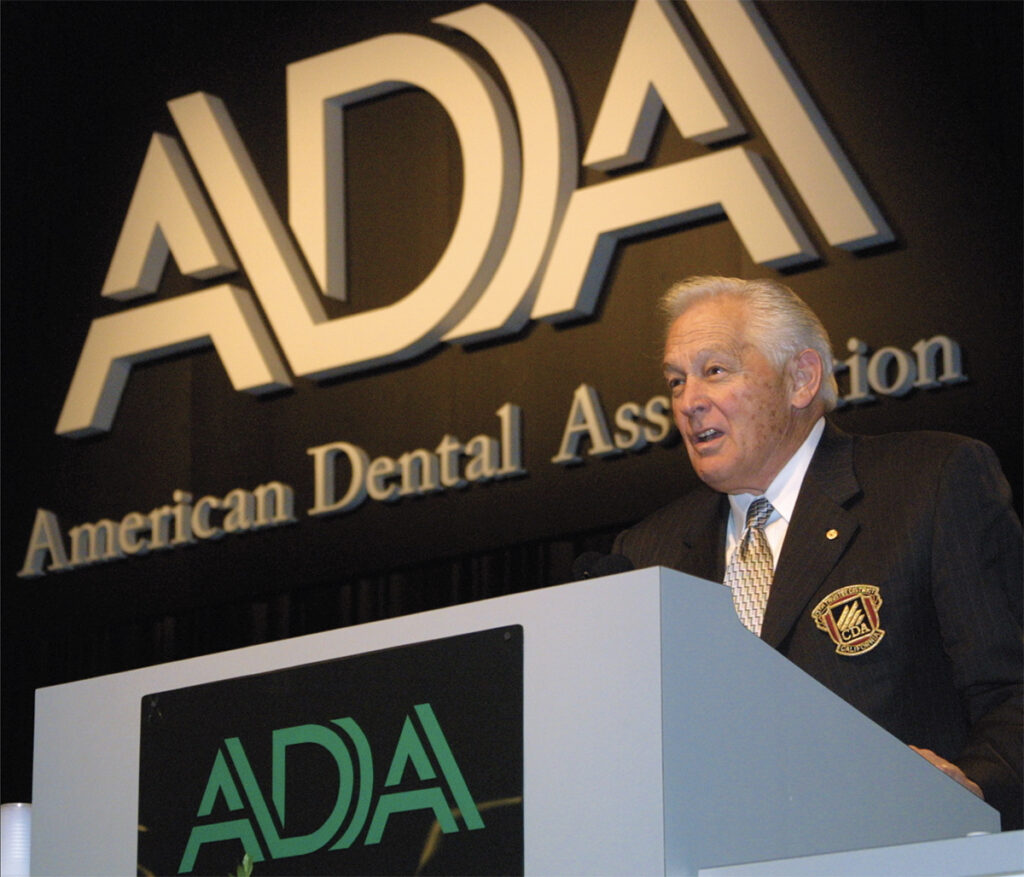

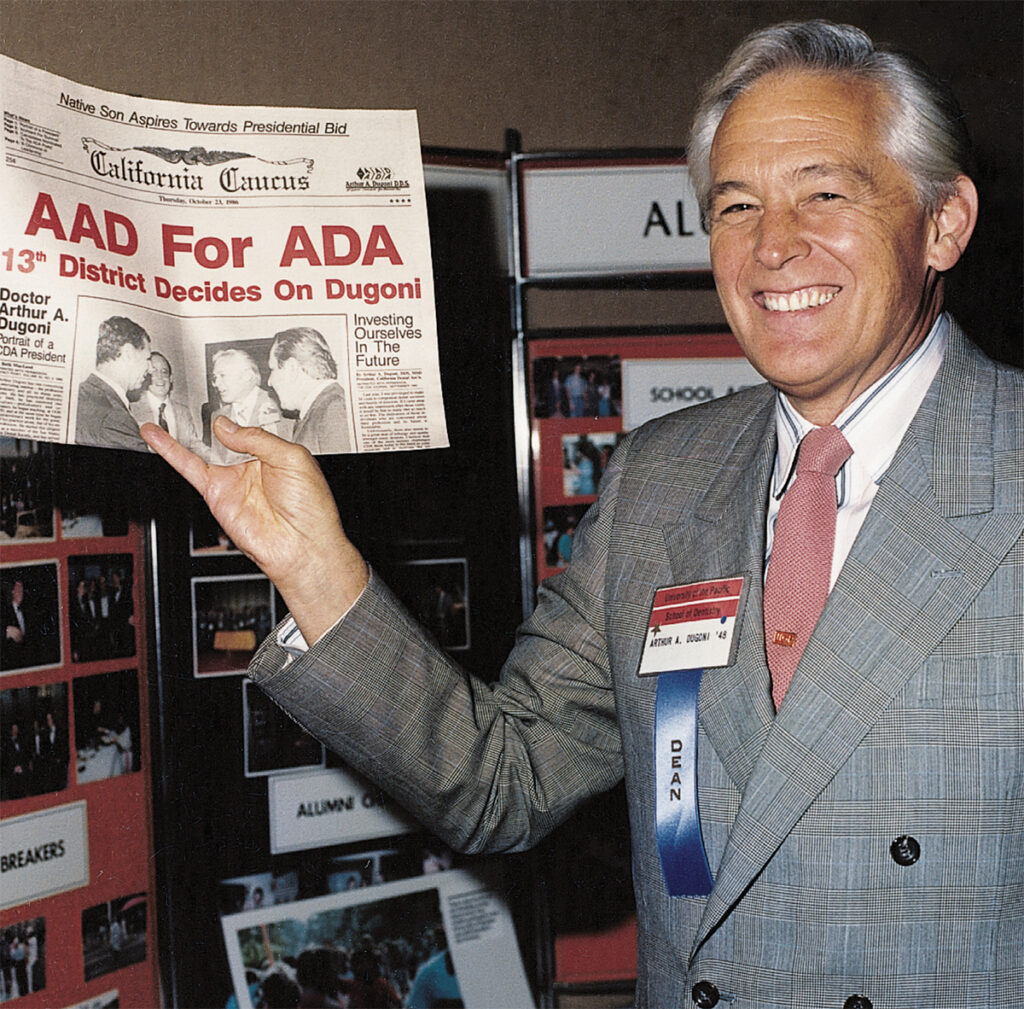

Dugoni was an overachiever’s overachiever: valedictorian of everything—his high school and dental school class—and president of everything—the P&S dental student body, first, and eventually, the California Dental Association, the American Dental Association (he was also ADA trustee and treasurer), the ADA Foundation, the American Dental Education Association and the American Board of Orthodontics. He was treasurer of the FDI World Dental Federation, where he instructed a global audience, and co-founder of The Santa Fe Group, a think tank aimed at improving oral health. As Gilbertson points out, “Art’s internal drive to do his best, to be the best, fueled by his cosmic energy and talent, produced a universe of achievements.”

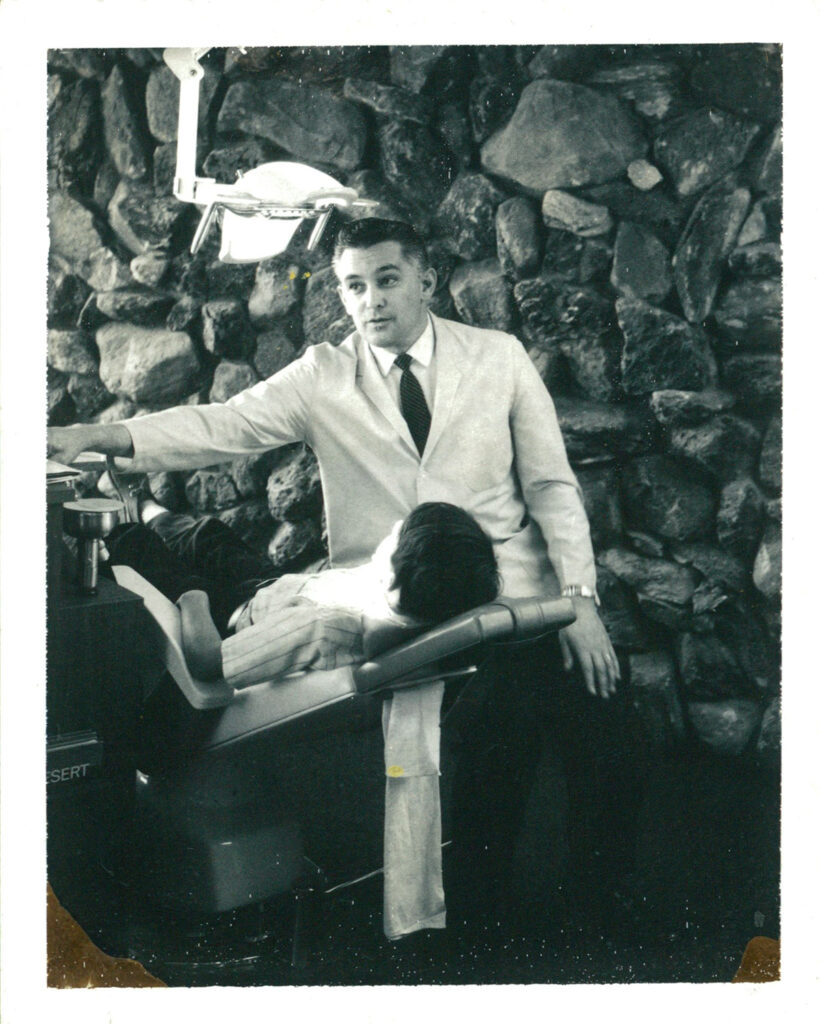

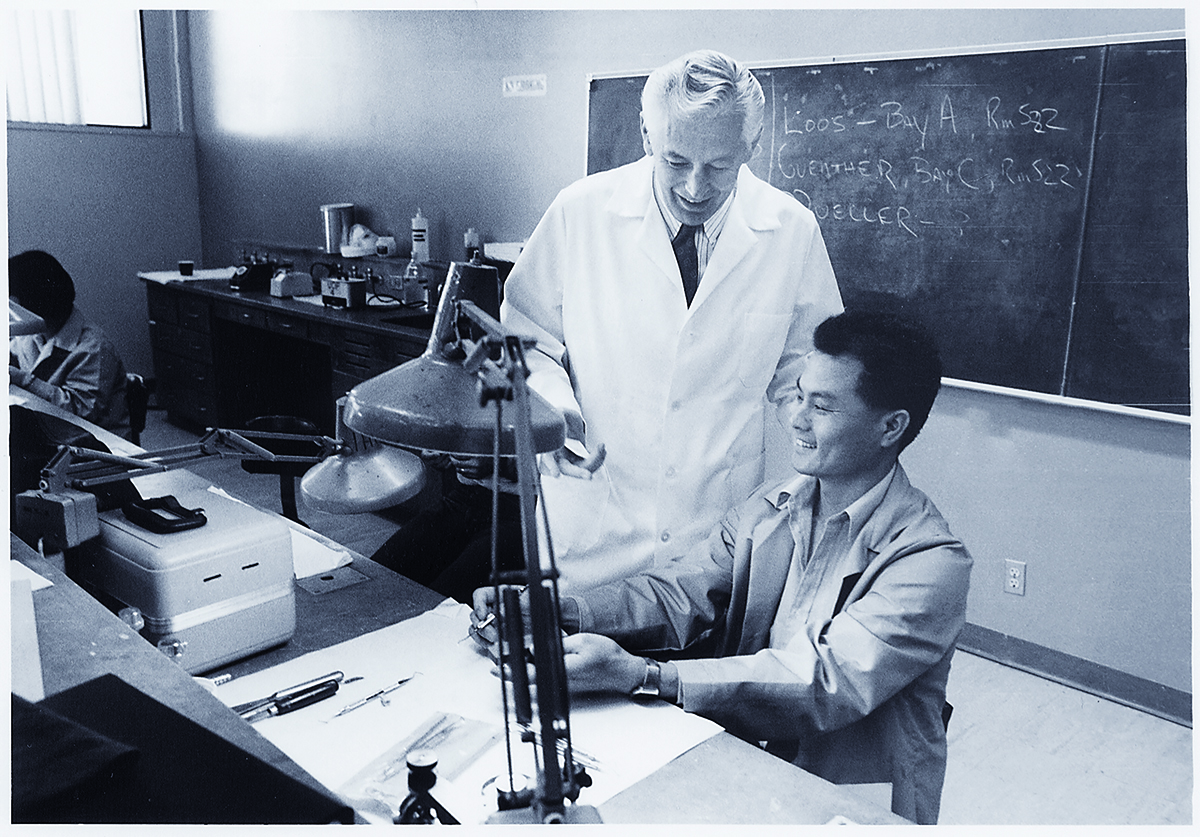

Dugoni loved to remind people that he had participated in every facet of dentistry. He had worked as a dental assistant, dental hygienist, dental lab technician, general dentist, pediatric dentist, orthodontist, dental school instructor (in all three disciplines), researcher, speaker, continuing education course presenter, board evaluator and administrator. This breadth of involvement ratified his sensitivity and wisdom, while its very intentionality also seemed to imply that his life’s work was foreordained. It was as if his background formed a chain and a correlation, an organic, binding growth pattern, upward and out, cell layer on cell layer, carrying him inexorably from the mailroom, as it were, to the proverbial corner office.

Dugoni also keenly felt linked to history, to his family history and Italian immigrant heritage—a classic American story—to the city’s history, and to his school’s history. He was proud to be a product of his environment: a San Franciscan, P&S graduate and dentist. His connections formed a continuum. He talked about his own mentors, including Dean Ernest Sloman, as if they were still conversing with him. And he reached out to potential protégés everywhere. Surprisingly, he never took his acclaimed, prodigious memory for granted, but reinforced it with diligent preparation. He read widely and constantly. Dugoni even rehearsed his celebrated ability to remember names. “Every year as soon as the class photo was available, he would have us develop brief bios on each student,” Nielsen says. “The dean would spend the night studying the material, and in the morning would have names of students, spouses and children committed to memory. And this would stay with him forever.”

Dugoni’s powerful example inspired thousands of us to do as Art did—get involved, of course, and become a leader; speak up; lend a hand; donate money; help someone; be friendly; remember people’s names.

“I learned many things from him,” says Dr. Richard Fredekind, former executive associate dean: “being well prepared for everything I did, taking care of all the details, listening first and talking second, the power of a smile and a pat on the back.”

Art Dugoni’s Energy

Dugoni’s deep interests, natural curiosity, inborn competitiveness, inexhaustible enthusiasm and hunger for excellence made him a tireless worker. Even when suffering from prostate cancer, he took treatments in the morning and got right back to his office. He was, in the words of Dean Smith, “always ‘on.’” He prided himself on needing only a few hours of sleep each night. If he never got fatigued, as Associate Dean for Institutional Advancement Craig Yarborough ’80 once asked him, “How do you know when to go to bed?” “When the work is done,” Dugoni replied.

He was an eloquent speaker, because he liked to talk and connect with people—he enjoyed having attention as much as giving it—because he had a flair for drama, because he carried a critical message and because he prized knowledge. He was as natural a student as he was a teacher and derived pleasure from consuming and communicating clear, useful information.

Dugoni’s energy, serving as a shield against doubt and discouragement, calibrated his performance across his 28 years as dean, and over time, it so finely tuned his leadership skills that they passed from an observable, measurable set to something felt, like an aura.

“Honestly, I was expecting a pleasant but perfunctory meeting with a 94-year-old,” says new University of the Pacific President Chris Callahan about the first time he encountered Dugoni, “where we would exchange pleasantries and best wishes. Instead, I was taken aback as he walked in, immediately commanding the room and the attention of everyone in it. You knew you were in the presence of a once-in-a-generation leader.”

Art Dugoni’s Optimism

Dugoni believed in people. He believed in their essential goodness, and he believed in their potential. This belief, driven by native good cheer and a quiet but deep religiosity, led him to equanimity, calm and conciliation. He expressed occasional anger not as an emotional reaction to perceived unfairness, but as energy in the service of change. Looking beyond others’ shortcomings, he was quick to forgive. He rarely experienced disappointment. In short, Dugoni was an optimist.

Optimism made Dugoni a peacemaker. He avoided arguments. “He asked me several times before I went off on campaigns to prove my point,” Chambers recalls, “‘Dave, do you really need another enemy?’”

Dr. Michael Alfano, former dean of New York University College of Dentistry and another founding member of The Santa Fe Group, says, “Art brought us gravitas, guiding us to our goals without ruffling too many feathers along the way.”

Dr. Anthony Caputo, a Tucson, Arizona anesthesiologist, graduate of University of Colorado School of Dental Medicine and veteran ADA 14th District delegate, was a student leader at the American Dental Education Association when he met Dugoni, who, of course, remembered him forever after. Years later, at an ADA House of Delegates meeting, during a heated debate, Dugoni offered his friend some advice: Give your best testimony and accept the outcome. “He looked at me with kindness and understanding,” Caputo recalls, “put his hand on my shoulder, and said, ‘Anthony, the wisdom of the House will prevail.’”

In The Alchemist, a parable of life’s journey, Paulo Coelho contends that when you resolutely follow a dream, “the universe conspires in helping you to achieve it.” In following his dream, Art Dugoni created his own universe. That universe is us.

Dr. Eric Curtis ’85 practices general dentistry and teaches college English in Safford, Arizona.